10 Learnings from the 10 Years After IARC’s Glyphosate Monograph 112

Marking a Dark Date in the Greed and Opportunism of NGOs, Activists and the Litigation Industry

French translation

Ten years ago this week, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) released the full Monograph 112, that included a decision on the carcinogenicity of glyphosate. The ten years of activism, opportunism and profiteering that followed this activist-manufactured event have reshaped the regulatory, agricultural and NGO campaign landscape for the next generation. It still stuns me to consider how a relatively benign substance and extremely important agricultural input could have been so easily hijacked by such a band of opportunists, cult ideologues and well-funded interest groups.

To mark this moment, in which I also played a small part, here are ten learnings from the ten years since IARC instigated what has since become a well-rehearsed activist playbook. Also listen to my discussion of these points with Professor Kevin Folta on his podcast, Talking Biotech.

1. That many in the American scientific community could easily be bought by the litigation industry

The perception of scientists and the research community as a whole used to be one of a field dedicated to discovery, revealing the truths and evidence and abiding by strict codes of conduct, integrity and the scientific method. When I revealed that a scientist who had enjoyed a considerable stature among his peers, Christopher Portier, had participated in the IARC glyphosate monograph working group on behalf of tort lawyers preparing lawsuits against Monsanto, there was considerable shock and outrage at his behavior. Portier was subsequently paid large sums by the US litigation industry to campaign globally against regulatory agencies that rejected the IARC findings. Deeper research revealed just how many scientists who had served on IARC panels had supplemented their income with lucrative litigation consulting fees (around $500/hour) for the glyphosate lawsuits. Most of them were members of the Collegium Ramazzini, and many of them, like Portier, had done no prior research or publications on glyphosate.

2. That IARC is not really part of the WHO or accountable to it, and is more of a political body than a scientific research agency.

IARC liked to frequently claim that it was a World Health Organization (WHO) agency, but as it began to come under pressure for its failures and conflicts of interest following the publication of the glyphosate monograph, it became clear that the WHO had no influence on this rogue agency (unlike how the UN was able to reorganize the IPCC following ClimateGate in the wake of the University of East Anglia email leaks). IARC is only accountable to its 30 member states and the foundations that pay its budgets.

IARC civil servants were spending more time coordinating personal attacks on scientists who challenged their Monograph 112 findings, threatening editors who published papers against them, corresponding with anti-GMO activist campaigners and monitoring the progress in the policy process to ban glyphosate. When American scientists who had served on IARC panels received Freedom Of Information requests (FOIAs), the head of Monograph 112, Kate Guyton, demanded that all IARC emails remain confidential.

3. That rules and procedures were not important at IARC (and lying was commonplace). It did not use the time, post Chris Wild, to do a root and branch reorganization.

In 2017 there were a series of exposés against IARC’s Monograph 112 and its inappropriate behavior. They were found to be editing the final glyphosate monograph after the meetings closed to make the conclusion, probably carcinogenic, more justifiable. Panel members admitted they were withholding data from the Monograph 112 meetings that would have cast doubt on the risks of glyphosate. They were ordering scientists involved in the Monograph 112 panel to not comply with transparency demands. IARC’s communications team was very politically engaged in the anti-glyphosate activism. Near the end of 2017, several American congressmen wrote to IARC with a series of questions and a demand for their director, Chris Wild, to come to Washington to testify. Wild not only refused to comply, his response to the letters was disrespectful.

In 2018, at the end of Wild’s term, the incoming director, Elizabete Wiederpass took over but only introduced some quiet reforms of the monograph program (Kurt Straif was retired and Kate Guyton was passed over in the leadership structure). But there were no major reforms of the hazard-based approach or the political activism. By 2023, with the aspartame monograph intervention (where the WHO’s JECFA was tasked with the risk assessment), it became clear that the Ramazzini-led political activism was still alive and kicking in IARC. They have returned to serving the litigation industry with a recent monograph on gasoline.

4. That the Ramazzini Institute is largely dependent on US funding (NIEHS and, now, the litigation industry). It has been used as a means to bypass national policies.

The Ramazzini Institute is a lab based in Italy and aligned with a global group of scientists who are members of the Collegium Ramazzini. They produce studies that challenge the consensus on environmental exposures (like their documents against the safety of glyphosate and aspartame) and many of their reports feed directly into the IARC monograph program, where many of the Ramazzini-affiliated scientists are actively engaged on panels. Funding for Ramazzini research came largely out of Linda Birnbaum’s office at the NIEHS (with contracts from 2000 to 2020 awarding millions to the small Italian lab). Birnbaum is a Ramazzini fellow.

“USASpending.gov shows Ramazzini listed in 13 different NIH contracts, through four different third parties, for nearly two million dollars since 2009. Since Birnbaum’s tenure at NIEHS began in 2009, that agency has directed at least $92 million in grant funds to fellow members of the Collegium Ramazzini; NIH has given over $315 million in grant dollars for Ramazzini fellows since 1985.” Source: E&E Legal

This money was spent supporting research used in IARC monographs that challenged US regulatory policies that were supported by the findings of the mainstream scientific consensus. In other words, Ramazzini and IARC became important tools for activist scientists to bypass the US regulatory process.

Then the money dried up and Ramazzini has since had to tap other sources, like the US litigation industry.

Some examples:

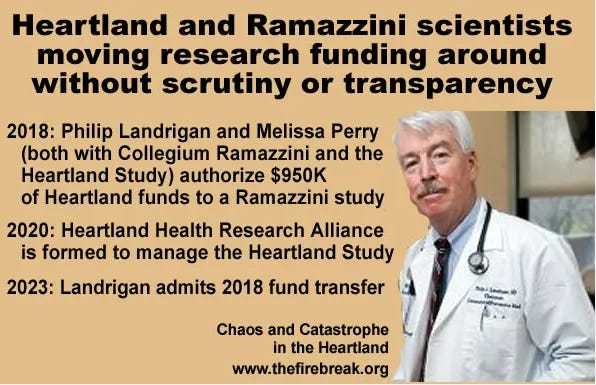

They were only able to raise about €300,000 for their Global Glyphosate Study (GGS), which held it up for several years. Head of Research at Collegium Ramazzini, Philip Landrigan, transferred almost one million dollars in 2018 as a lifeline for the GGS from money that US law firms had donated to the Heartland Health Study (that he was also directing) via his academic institution, Boston College. He only acknowledged the transfer in 2023 when new management at the Heartland Health Research Alliance informed him that his transfer was illegal and unethical.

When the GGS was finally published in 2025, with the promotion (advocacy) of the paper provided by Mercury Films, an organization run by Jennifer Baichwal, director of the anti-glyphosate film, Into the Weeds. This film and subsequent campaigns featuring it have been funded by the US tort litigation industry.

5. That the media was more interested in attacking industry than defending facts. A fear of being identified as “pro-Monsanto” was behind the lack of objective reporting.

When Reuters journalist, Kate Kelland, published a series of exposés on IARC’s mishandling of evidence and the publication process of Monograph 112, she won awards. She also received relentless waves of personal attacks (as did Reuters) for being Monsanto shills, forcing her to change news desks. She eventually left Reuters. This is not uncommon. In my standing up for farmers and their right to access an effective technology for sustainable farming, I have also been frequently attacked and have also paid several professional prices.

No journalist with hopes of a career in the media will dare stand up and expose these activist shenanigans given the leverage these groups have in punishing them. In the last ten years, glyphosate reporting has given us a textbook demonstration of how the media is not about reporting facts and evidence, but about presenting what it perceives the public wants to hear (and what will cost them as little flack as possible). Donald Trump has learnt this and exploits this media fear and weakness to the maximum.

6. That the La Jolla Playbook is an effective strategy for the litigation industry, NGOs, scientists and academics (and that adversarial regulation is an effective, non-democratic policy tool).

The 2012 conference in La Jolla, organized by Naomi Oreskes and the Union of Concerned Scientists, brought together a group of activist NGOs, lawyers and academics. They looked at the (successful) strategy used against tobacco companies to bring them to the table (and to their knees) and strategized how to apply this approach against other industries. The case they were looking at in La Jolla was to tobacconize the fossil fuel industry, attacking them with a relentless series of lawsuits (for causing climate change) coordinated with activist smear campaigns (like Oreskes’ “Exxon Knew” campaign) until these companies either went bankrupt or changed their business strategy.

Early attempts by the New York AG to subpoena ExxonMobil showed that the process would be harder, costlier and more time-consuming. But the La Jolla Playbook was applied against glyphosate, with law firms, NGOs and a group of Ramazzini scientists targeting Monsanto until, as Bayer, they settled for $11 billion. That was not enough for the voracious tort lawyers’ appetite, so the Playbook is still being applied until glyphosate is banned. A similar attempt has also been made on banning talc by suing the hell out of J&J, and, with less immediate success, Coca-Cola, on its use of aspartame. The lawyers, NGOs and scientists are now planting seeds in the greener fields of ultra-processed foods and mobile phone cancers.

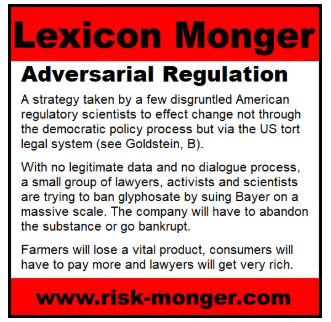

Within the scientific community, another term has been openly discussed in papers and conferences called “adversarial regulation”. Retired US regulatory scientists like Bernard Goldstein and Christopher Portier, perhaps frustrated by years of lobbyist interventions in the regulatory process, prefer the adversarial (litigation) approach of scientific advisers working with law firms to persistently sue the corporations making the targeted products or substances. According to Goldstein, this approach has proven to be more effective in changing markets and practices than the regulatory approach. It has also proven to be more profitable for the scientists involved. One small detail though is that adversarial regulation circumvents the democratic process.

7. That litigation finance is profiting from a complex web of tort industry bottom-feeders

The tort law industry has evolved in the last two decades from the strip-mall huckster with his face on a billboard hustling rear-ender victims to one of large offices with teams of experts, lobbyists and private jets. Scaling up the business to an industry level demanded high amounts of financial support, but following the 2008-09 financial crisis, the Dodd-Frank regulation made bank loans to uncovered borrowers like tort law firms practically impossible. Litigation finance developed out of this vacuum as a type of non-transparent loan shark business open to the shadowy side of dark investments from institutional and sometimes foreign investors. While very little is public about how much litigation finance “banks” are taking from settlements (before the plaintiff gets any payment), some published results puts the number at 25%. Often the return on investment for these quasi-banks includes a percentage of the payout or settlement.

That number though is larger when the complex web of litigation industry bottom-feeders are added to the mix. As cases got larger with class action lawsuits and multi-district litigations, a larger ecosystem of misery merchants developed:

all of those late-night TV ads and online marketing are done by specialist firms

these firms then funnel the potential plaintiffs onto specialist consultancies who then interview, handle and rank the candidates

the candidates are then traded on a, sorry to be blunt, victim exchange.

As the processing and sale of potential plaintiffs takes time to generate a return, these litigation industry bottom-feeders require a considerable amount of up-front capital which can only be funded by non-transparent extortionists in the litigation finance industry.

If companies would ever have the courage to hold their ground and stand up to these litigation industry tactics (but with skittish institutional investors holding most of the shares in these corporations, they never will), the entire litigation finance Ponzi scheme would come crashing down.

8. That the anti-industry narrative is intense in popular Western (post-capitalist) culture. The word “Monsanto” became much more toxic than its chemicals.

Have you noticed that some of the recent punitive damages awarded to plaintiffs in US tort cases have been in the billions of dollars in lawsuits where liability is anything but cut and dry? While it is hard to value a life, juries have no problem coming up with extraordinary numbers to make the companies pay. In a post-capitalist world, the corporation is vilified by radical Marxist factions within NGOs, the academe and the media using the courts to try to sue capitalist enterprises out of existence.

At a time when Western societies have never benefited more from industry innovations, living better, longer and more comfortable lives, the public narrative demonizing the corporations has gotten out of control. Much of this is due to the shift in the funding mechanisms that are influencing the popular communications landscape. NGOs, researchers and media groups are getting large donations from a well-endowed, professionalized philanthropic industry while industry funding of the media and academe has largely dried up. When foundations managed by fiscal sponsor agitators give tens of millions of dollars to NGOs to run campaigns to be published in mainstream media groups these same foundations are funding based on reports they produced attacking industry processes, is it any wonder the public is buying into the anti-capitalist rhetoric (while still enjoying the benefits). As the MAHA movement in the US bears testimony, this dog and pony show has also worked its way into the regulatory agencies.

When you control the narrative, the truth doesn’t matter. Glyphosate is an essential part of sustainable agriculture allowing farmers to use no-till practices and protect their soil with complex cover crops while using fewer pesticides overall. Glyphosate has not been found to be a significant health risk by any government risk assessment agency in the world. These are facts that our post-capitalist, anti-industry narrative is able to efficiently smother.

9. That farmers are a very small part of the voting population and their interests are secondary.

Two generations ago, most people would have either have grown up on a farm or had relatives who worked the land. People understood and sympathized with the challenges farmers faced. Today, many consumers assume the food system is simple and should adhere to certain naturopathic dogma that aligns with their political ideology. So consumers demand that their food is grown pesticide-free, GMO-free, with no industry-researched synthetic inputs or fertilizers and believe these non-scientific demands can be met in the fields. And regulators are beginning to bend to their will given that agricultural community is no longer a major political or electoral force.

Worse, the food industry is starting to bow to what they perceive as consumer pressure and demanding that farmers comply with their marketing-driven demands (eg, organic, ESG, all naturally-grown …). An evidence-based policy approach needs to be enforced but there is no will or courage given the force, funding and opportunism coming from the deftly coordinated activist-litigation-academic onslaught. The farmers will have pay the price.

10. That this campaign was never about sustainable farming, the environment or public health but a means to fight GMOs.

Glyphosate has been called the herbicide of the century for good reason. It is a unique substance that has enabled a sustainable revolution in farming by allowing farmers to protect their soil via larger no-till practices and the use of complex cover crops (that could be terminated without tillage, soil erosion or biota destruction). It is inexpensive, off-patent and after three decades of widespread use, still fairly effective. The organic food industry lobby has no similar substance, hence their motivation to undermine its reputation. But this is not enough of a reason to justify the persistent campaigns against the herbicide over the last 15 years.

To understand the motivation for this irrational movement against glyphosate, we have to remind ourselves of the activist strategy in 2013-14 in the US. During this time, there were intensive NGO campaigns against GMOs, Monsanto and pesticides in general (at the time dominated by neonicotinoids and the campaign to save the bees). But things were not going as planned:

The March against Monsanto events were passing their zenith

the retraction of the Séralini paper removed their only scientific argument

the campaigns in certain states to have GMOs labelled on all food products had just failed.

In 2013, the US Congress passed Section 735 in the Consolidated and Continuing Appropriations Act, protecting farmers from being sued for planting GMO crops.

The anti-GMO campaign was defeated so the activist groups needed a new tactic.

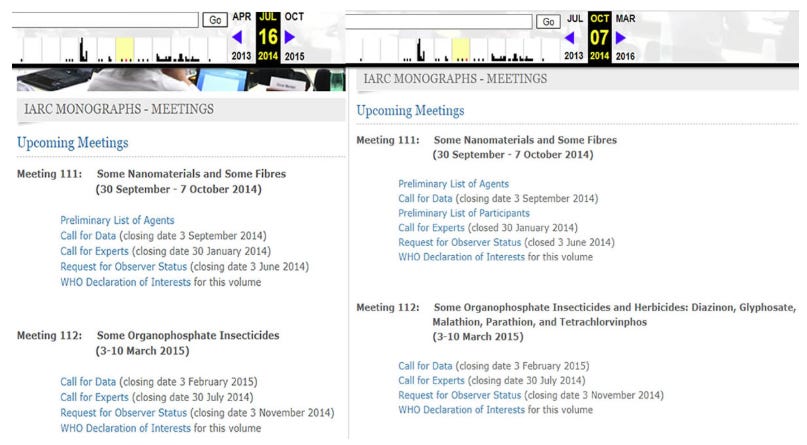

As one of the key benefits of GMOs, particularly for GM maize and soy crops, was that they could be made to be herbicide-tolerant, the focus then shifted to the herbicides applied to the GM crops. There was a clamor to take Roundup to the courts … but for that you would need to produce evidence other than just activist outrage. In 2014, IARC had planned Monograph 112 (announced on July 16, 2014) to only be on “Some Organophosphate Insecticides”. Less than three months later, glyphosate was quietly added to this monograph at the time when Chris Portier, a key leader in this campaign, had been meeting with several tort law firms. He would later be a key figure with these firms in the lawsuits against Monsanto.

It doesn’t take much to see how this entire anti-glyphosate campaign was due to a pivot by the defeated anti-GMO activists. It had nothing to do with sustainable farming, the environment or public health. In fact, the drive to ban or tobacconize glyphosate would be detrimental to these ambitions.

Once again, the truth doesn’t matter for these snakes.

So we learnt a considerable amount in the ten years following the publication of IARC’s glyphosate monograph. But I fear we haven’t yet learnt how to manage these activists, academics, foundations and tort lawyers so that such travesties don’t happen again (indeed, these opportunists are executing from a playbook). Here are ten suggestions of what is needed (knowing full well that executing these measures would take an enormous amount of courage and steadfastness that is lacking in our present political arena).

Ten Ways to Fix this Mess?

The US needs tort reform (including and especially the litigation finance industry).

Foundations need to be forced to become transparent and the dark, donor-advised funds need to be abolished.

Scientists who are accepted into the Collegium Ramazzini should be ostracized and should not receive public funding until this closed group of activist scientists adopts and implements a legitimate ethical code of conduct.

NGOs need to also adopt ethical codes of conduct and any transgressions should be sanctioned (rather than celebrated).

Media groups need to be transparent on their funding and cooperation with activist groups.

The IARC monograph program needs to be shut down (or at the least, have it become risk-based rather than hazard-based).

Monograph 112 needs to be retracted. There were violations in ethical conduct at almost every stage of the process and it is still being used by opportunists in the litigation industry.

Rather than more science communication, we need more communication about science (which has been widely abused in our public dialogue, especially now by grifters like RFK Jr and his “gold standard” of science).

Industries need to work together to stand up to these activist onslaughts and stop pretending that, as the second slowest zebra, they will never be affected by the relentless tobacconization playbook implementation.

The WHO needs to be reorganized so that it is no longer representing a cornucopia of health interest group factions, but one dedicated to providing support and coordination to national research organizations and health campaigns.