A Tale of Two Retractions

The reactions to two academic paper withdrawals says a lot about who we are and how we think about science

See Hungarian and French translations

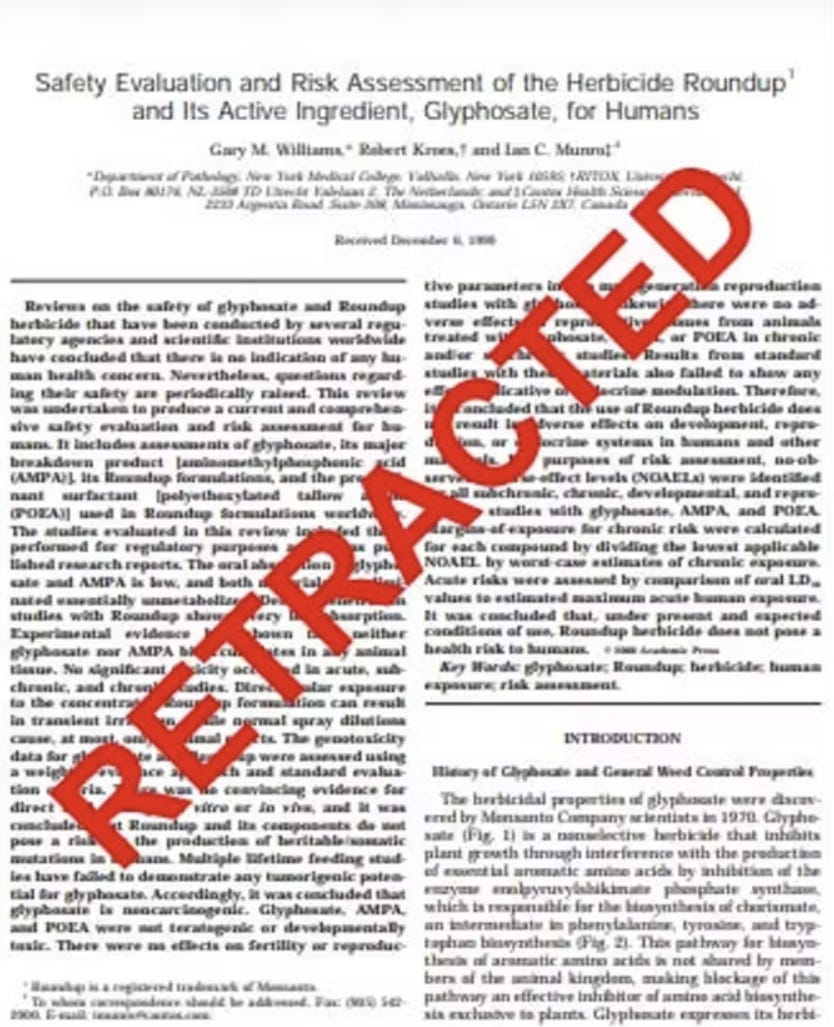

This week two scientific papers related to two highly media-driven political issues were retracted. These rare events concerned a paper published in 2000 by Williams et al on the safety of glyphosate and one by Kotz et al published last year on the predicted economic costs from climate change. Both retractions generated a significant amount of social amplification across the wide range of stakeholders and special interests. The retractions though were for completely different reasons and speak volumes about the nature of the debates and the actors they are associated with.

A retraction is a stigma, representing a failure in research, a lack of proper scrutiny in the peer review process or worse, fraud and opportunism. But a retraction is also part of the scientific method, the consequence of continuously checking and testing claims to verify their robustness. This self-correcting nature separates science from political ideology or religion. Developments in technologies, methods and paradigms can make past theories obsolete but these advances should be celebrated as science continues to improve and progress.

Importantly, how we react to retractions reflects what we expect from science. Is science about discovery or a tool to advance policy and special interests? Does a scientific publication in a journal define the truth or is it but a mere step in the progress of the body of knowledge? These two retractions show that there is more division in how people perceive the role of scientific evidence in the issues we manage.

Getting Climate Change Costs Wrong

Retraction Watch recently reported on the retraction of a paper entitled: The economic commitment of climate change published in Nature in 2024 by researchers from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) in Germany. Several errors in the calculation of the data, methodology and a failure to properly estimate the uncertainty of data projections were reported. The Journal had already made some corrections after the paper’s initial publication but in this case, the authors accepted that the errors were too great for any further correction and accepted the paper’s retraction. They stated they will revise and resubmit the research at a later date.

The article was controversial as it claimed that climate change would cost the global economy three times more than what had previously been predicted, lowering global GDP by 62% by 2100. It was cited 168 times in other articles and used by climate campaigners to justify their demands for increased public spending on climate mitigation actions.

The retraction was about getting the data right, reflecting how much of the climate debate has been disagreements on the level of climate change, the causes, the reliability of the models and the consequences for humans and the environment. It serves as one more cautionary tale about how the climate campaigners need to temper their catastrophic claims and engage more with skeptics. Climate scientists have come across as arrogant and intolerant toward those who question their research claims. Just last month, at the UN’s climate conference, COP30, a group of nations passed a declaration to fight climate disinformation which included stopping skeptics from questioning the findings of climate scientists.

Science did its job here, even if it went against the agenda of the global climate campaigns.

Retracting Industry Science

The second retraction was quite different as it was not based on bad data or methodology, but rather questioned the scientific integrity.

The paper entitled Safety Evaluation and Risk Assessment of the Herbicide Roundup and Its Active Ingredient, Glyphosate, for Humans by Williams et al, published in Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology in 2000, presented evidence that glyphosate was safe. It relied on unpublished industry data which was more accepted 25 years ago when Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) techniques had removed questions of special interests. As well, in disclosure documents obtained during preparation for lawsuits against Monsanto, an email revealed that they were involved in ghost-writing this paper. This practice was also more accepted 25 years ago.

This was a righteous retraction based on questions of scientific integrity. It was prompted by an article published just three months earlier by Naomi Oreskes (ghost-written by a student and funded by the Rockefeller Family Fund, a foundation that has financed a large part of Oreskes’ activism) urging that as the Williams paper still commanded an influence on the debate, it should be discredited. Oreskes is the architect of the La Jolla Playbook that seeks to achieve policy change not through democratic processes but by using the litigation industry (which funds her) to sue industries out of existence … so her skin is this game is a bit “rashy”.

Also interesting is that the co-editor of the journal that retracted the paper is now Martin van den Berg. Martin is an old warrior in the battles against industry, coming to prominence in the early 2000s as the activist scientist running rudimentary biomonitoring blood tests to support NGO campaigns against brominated flame retardants. So perhaps we should call this a “self-righteous retraction”.

A Nothing Burger

EFSA, the European Food Safety Authority, reacted to this evidence two years ago, saying that the involvement of industry was declared and the nature of how the paper was produced had no scientific influence on the question of the safety of glyphosate.

EFSA reviewed over 3000 publications in determining that glyphosate was safe for reauthorization.

Like the climate paper, the retraction of the Williams et al paper reflects the nature of the glyphosate debate. It is not an issue of scientific data or methodology, but rather on what is perceived as research integrity. The anti-pesticide groups see this as a battle between good and evil and find any information that they perceive as impropriety as cause for action.

The scientific data claiming health risks from glyphosate are extremely weak and not accepted by any national risk assessment agencies or the wider scientific community. So the campaigners have to bring up the ghost of Monsanto and a 25 year old paper to stoke public outrage. Perception matters more than scientific facts, so this retraction will likely be used in US tort lawsuits as a means to show that all of the scientific evidence must somehow then be corrupted.

Science didn’t do its job here but rather bowed to the political agenda of a group of fear-mongering activists funded by the US litigation industry and fiscal sponsor consultants directing large volumes of philanthropic wealth into a special interest campaign.

Pawns and Preachers

We find ourselves in a Brave New World where scientists, their research and the organizations they work with have become pawns in policy games, manipulated by activists, the media, the litigation industry and companies seeking opportunities from regulatory transitions. Worse, the journals these scientists once relied on to allow robust scientific debate have become battlegrounds of propaganda waged by the vulgar, unscientific special interests and editors with political agendas.

The scientific method is struggling to survive as the activist playbooks are being implemented. A retraction is a weapon for a campaign rather than a means for the institution of science to self-correct and advance the body of knowledge. It has, instead, become the body of activism. As the peer review process has been dying a slow death, the political manipulation of the retraction tool is but one more dagger into its heart. Let’s hope this is Martin van den Berg’s last assault on the reputation of science.