Citizen Bot

The Latest Activist Attempt to Make Uselessness More Efficient

It’s happening already.

I just received an invitation to participate in a citizens’ panel (the activist left’s latest tool to advance their political agenda) on the EU’s Green Deal and wider environmental issues. The twist here is that this public consultation will be completely managed by artificial intelligence (AI).

The event, organized by a small, rather inactive group called Club Climate Europe, is called “Leveraging the EU Green Deal: 2040 climate goal, and climate and defense” (sic). They are using an AI-powered facilitator called “Natter” to engage with participants and immediately produce a “citizen-driven” report with policy recommendations to be submitted to decision-makers in the European Commission and the European Parliament (or their AI contact points).

Nattering On

The AI app running this “public” engagement, Natter, pronounces its efficiency and exceptional reach with enormous confidence:

Natter allows tens of thousands of people to connect, ideate and respond to key questions, all at once. Instantly capture and analyze millions of your peoples' ideas and responses through real-time video conversations and AI. Source

It is hard to learn much more about Natter except that the organization is UK-based, small, founded in 2021 and is supported by a lot of big funders via Village Global, the venture firm backed by Reid Hoffman, Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, and Mark Zuckerberg. I even asked AI to tell me more about Natter but got very little.

The objective of this AI app is to replace surveys, focus groups and questionnaires with real-time engagement. Their website claims:

Our inclusive technology connects employees in video conversations, poses your questions and analyzes the responses. All in under an hour.

This sounds impressive, but is such efficiency welcome in complex risk-policy debates?

A Legitimate Approach or an Activist Validation?

Natter drew up the 30 major discussion questions on Green Deal climate issues (without, apparently, any human editorial supervision) to guide the one-hour real-time citizens’ panel (less than two minutes per issue). I understand that AI has massive processing power, but are humans, in real time, capable of expressing meaningful ideas across such rapid information flows?

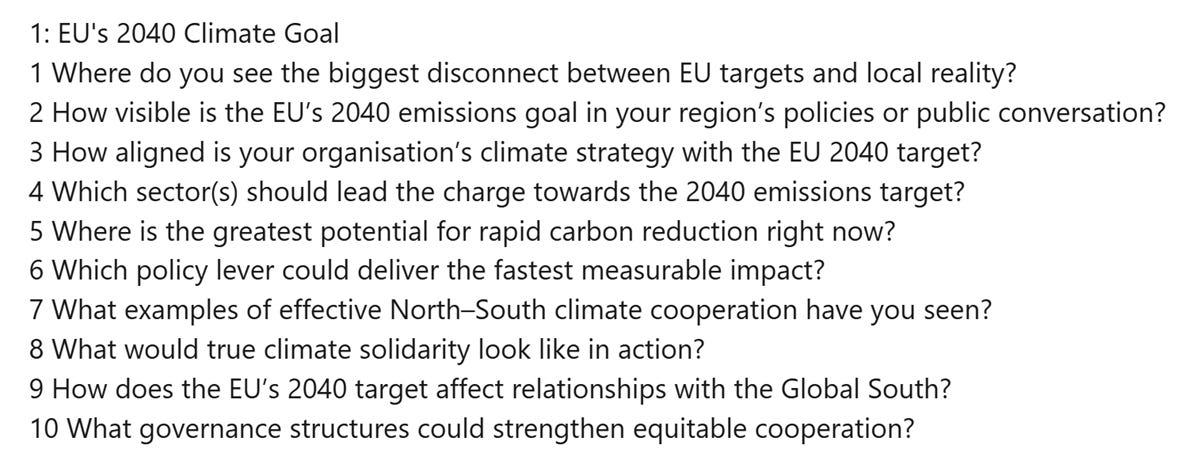

Here, for example, are Natter’s ten suggestions for 20 minutes of consultation on the EU’s 2040 Climate Goal:

Each of these points should take at least 20 minutes in order to create a good impression of the widest possible sentiment from a broad range of citizens. It would take ten minutes to properly define concepts like climate solidarity or equitable cooperation (assuming that the citizens participating in this panel are not all experts in social justice climate activism). This begs a series of questions:

How much of the 20 minute time limit will record actual ideas and how much had been algorithm-driven before the citizens’ panel consultation?

Are humans now being roped in to superficially validate what the policy activists want their AI tools to pre-conclude.

How many non-experts does it take to validate their precautionary policy approach? 30? 300? 3000? How will we know?

With the tight time constraints, is the AI bot the only entity engaging with the citizens in a rapid-fire interview? Can participants draw off of each other’s ideas?

At what point will the AI bot draw inferences from what may be random or unrelated points?

The results of a survey or interview always depend on the questions you ask. The Club Climate Europe fed their bot with the objective of asking ten questions on whether increased military spending in Europe will act against the EU’s climate ambitions. Of course it will! But this activist group, cynically, wants to pretend this conclusion was a result of a citizens’ panel and that the people have spoken.

AI can be useful for scenario building to aid in the decision-making process. But when an organization like Club Climate Europe, itself a sham body, tries to use it to advance their agenda while pretending to have performed a democratic consultation, we cross over into the realm of the deceitful and the manipulative. As they do whatever they can to win their campaigns, AI is just one further area where we need to keep the activist zealots in check.

AIy yAIy yAIy !

Citizens’ panels have always been a controversial idea. Activist groups, who feel that the expert-based policy approach has worked against their interests (relying more on facts and evidence than public concerns, ie, fears, and emotional ambitions), have been demanding more public engagement tools in the risk assessment process. NGOs feel that the general public is more easily scare-able (they should know) and thus more willing to validate the activists precaution-based policy recommendations.

There have been some rather tragic examples of how citizens’ panel advice has pushed policymakers down intolerable rabbit-holes, like:

The French government set up its “Citizens’ Convention for Climate“ in 2020, and one of the key recommendations this citizens’ panel demanded was to ban the rollout of 5G.

When the UK government consulted its citizens to name its new polar research vessel, an overwhelming majority demanded that the ship be christened: Boaty McBoatface (garnering four times the votes of the second choice).

The European Parliament, Council and Commission launched the Conference on the Future of Europe in 2021. It was an expensive one-year Europe-wide participatory experiment that was quickly forgotten (and abandoned).

I once described the citizens’ panel / assembly approach as the liquidation of leadership. It may sound noble to declare trust in a selection of the public and consult them on particular policies (like how to save the planet), but it assumes the selected public is a) representative and b) rational. “Asking an ad hoc group of risk-averse docilians with time on their hands to tell our leadership what to do is anything but responsible and accountable.” In the last five years, we have seen an abrupt abandonment of such direct citizen engagement.

Using AI tools to run citizens’ panels (where algorithms dominate in the editing of real-time citizen contributions) is merely making this uselessness more efficient. But environmental activists see it in another light, as a validation tool to advance their emotion-based fear campaigns.

Most of the people who would volunteer to join a citizens’ panel or assembly on an issue like climate change already have a concern or an interest (while the broader public does not have the time or the interest). These engagers have likely been scared by activist campaigns (or are members of the NGOs) and are demanding action. The best citizens’ panel is an election and as the global votes held in 2024 demonstrated, a good majority of the citizens are not aligned with the environmental activists’ agenda.

The objective of a citizens’ panel is to elevate the voice of those closest to the activist campaign talking points, thus validating the precautionary policy strategy. What AI does is merely amplify the fear-mongering with algorithmic validation and the sheer confidence in nonsense that only a bot can conclude.

Like most AI applications, the technology still needs time to improve (even the useless ones).