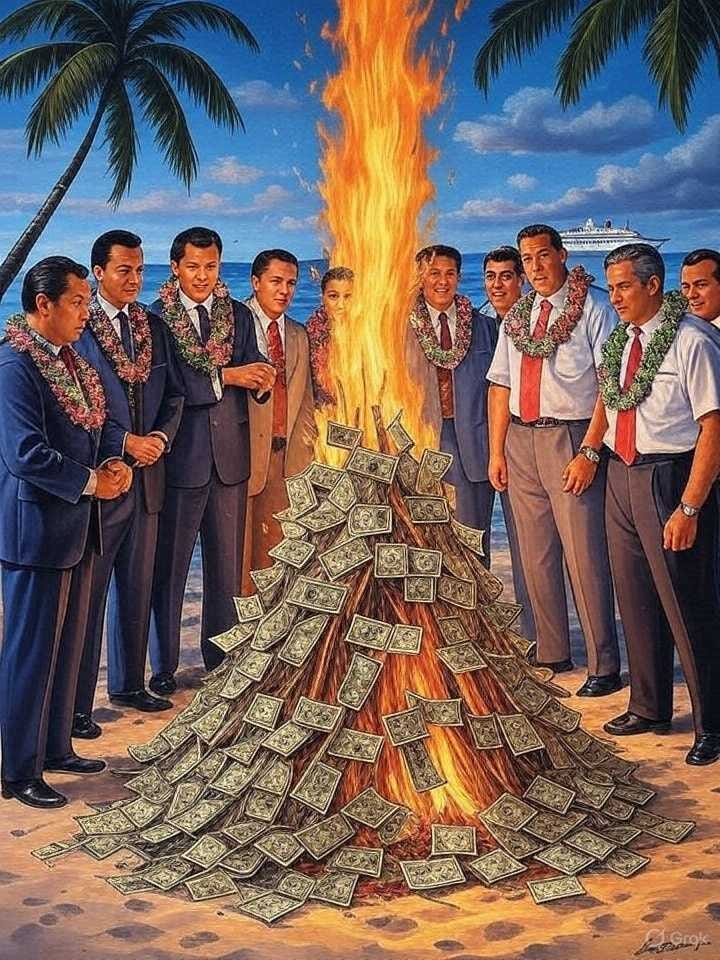

Hawai’i’s Latest Green Cash Grab is Cruising for a Bruising

Cruise industry targets Hawai‘i's unconstitutional 'Green Fee' in court.

Hawai‘i has long depended on the lifeblood of tourism. Families fly into Waikīkī, honeymooners trek to Maui, and—crucially—nearly 300,000 visitors a year arrive by cruise ship. In 2023 alone, cruise tourism pumped $639 million into the state’s economy, generated $116 million in tax revenues, and supported nearly 3,000 local jobs.

So why would Hawai‘i’s lawmakers choose to kneecap this vital economic sector with an unconstitutional tax scheme?

That’s the question at the heart of a lawsuit just filed by the Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA) and three local businesses to block the state’s so-called “Green Fee.” Proponents of the tax are pitching it as a “landmark initiative” to protect Hawaiʻi’s climate, environment and communities. In reality, it’s a blatantly illegal, punitive tax on Hawaiians that mistakes state-sanctioned plunder for environmental stewardship.

Act 96: A “Green Fee” in Name Only

The law under challenge, Act 96, signed this spring by Governor Joshua Green, imposes an 11 percent “climate impact fee” on gross cruise fares, prorated by the days a ship spends in Hawai‘i waters. Counties may tack on an additional three percent, meaning cruise operators — and ultimately passengers — will face a 14 percent surcharge simply for docking in Hawai‘i.

Unlike traditional port fees, which pay for actual services — dockage, security, tugboats, waste management — these new surcharges are untethered from maritime needs. Instead, revenue is earmarked for a grab-bag of unrelated “green” projects like native forest restoration. That makes Act 96 not only poor policy but plainly unlawful.

Three strikes against the Constitution

Act 96 is illegal on its face for three simple reasons. First, it violates the Tonnage Clause. The Framers of the Constitution barred states from levying charges for the privilege of entering, trading in, or lying in a port. The Supreme Court has consistently struck down disguised taxes on shipping, most recently in Polar Tankers v. Valdez (2009). Yet Act 96 does exactly that—tying fees directly to the number of days a vessel docks in port.

Act 96 also runs headfirst into federal preemption. The Rivers and Harbors Appropriation Act of 1884 prohibits states from collecting “taxes, tolls … or any other impositions whatever” on vessels “operating on any navigable waters subject to the authority of the United States,” except for narrow service-related fees. Hawai‘i’s proposal fails that test outright, because it’s a revenue scheme rather than a reasonable fee.

Finally, the proposal runs afoul of the First Amendment, forcing cruise lines to advertise their compliance with the illegal tax regime in marketing materials and notices posted onboard. Simply put, Hawai‘i can’t compel cruise lines to say they’re following a rule the state has no authority to enforce in the first place.

Punishing local business

Critics of cruise tourism often caricature the industry as faceless corporations, but this only exposes their cold indifference to the Hawai‘i small businesses, including three of the plaintiffs, whose fates are tied to cruise arrivals.

Honolulu Ship Supply earns more than half its revenue by provisioning cruise vessels—supplying fresh produce and technical parts and providing waste management. Meanwhile, Kaua‘i Kilohana Plantation hosts cruise excursions featuring train rides and luaus that keep hundreds of Hawaiians employed. Some local businesses could be totally crippled by the new tax. For example, Aloha Anuenue Tours derives all its income from cruise passengers visiting the Big Island.

If ships skip Hawai‘i or if passengers have less money to spend because hundreds of dollars are siphoned off in new taxes, these businesses — and the workers they employ — will be the first to suffer.

Critically, the economic ripple effects are poised to be enormous. According to Oxford Economics, Hawai‘i’s high-minded environmental proposal could cost the state up to “$320 million in output, almost $190 million in GDP, around 1,400 jobs, $100 million in wages, and nearly $60 million in tax revenues.” In short: Hawai‘i’s revenue-raising scheme will likely lose money.

Faux environmentalism

Some defenders of Act 96 argue that higher fees are needed to offset the environmental footprint of cruises. But this betrays a broader problem: the habit of treating punitive taxation as climate policy.

If Hawai‘i wants to address coastal erosion or invest in climate resilience, it should do so through its general budget—debated openly, applied broadly, and subject to political accountability. Singling out one disfavored sector, and only its out-of-state visitors, is not environmental stewardship. It’s opportunism.

Moreover, Hawai‘i already extracts substantial revenue from tourists through hotel taxes, general excise taxes, and port fees. The cruise industry pays millions each year–often in excess of $100,000 per voyage–for dockage and other services.

Layering on a constitutionally dubious surcharge only risks driving visitors elsewhere. Far from protecting Hawai‘i’s environment, that will hollow out the very economy that funds sustainability programs.

A Necessary Course Correction

Hawai‘i’s government has overreached. In its zeal to launch the nation’s first “climate impact fee,” it has trampled on constitutional safeguards, jeopardized local livelihoods, and ignored the hard economics of tourism.

The plaintiffs are right to challenge Act 96. Their case is about insisting that responsibility be exercised lawfully, rationally, and fairly. If Hawai‘i prevails, other states may be tempted to follow suit—opening the door to a patchwork of unconstitutional local levies on interstate commerce. That would be disastrous for maritime trade and tourism alike.

By contrast, if the court strikes down Act 96, it will reaffirm a principle as old as the Republic: states may not use their ports as tollbooths for unrelated political ambitions. That’s good law, good economics, and common sense.