Ian Urbina: Journalist Turned Activist

How a once-respected New York Times reporter became an unserious person

As newspapers bleed cash and lose subscribers to new media, editors are increasingly turning to alternative sources of revenue and content alike, often from mercenary freelancers and politicized “foundations” that act less like fact-finders and more like activists. This has attended a change in how journalists see themselves. Notions like balance and objectivity are treated as quaint and archaic, and this new breed of journalist-activists openly declare their biases and use their platforms to manipulate public perception—often at the behest of wealthy donors who now bankroll their work.

No reporter better characterizes this devolution than ex-New York Times scribe Ian Urbina. Known most recently for lurid, guerrilla journalism that maligns seafood companies as enemies of human rights around the globe, Urbina brands himself a truth teller, a renegade exposing a scandal most journalists won’t cover, amplifying the efforts of “vigilante conservationists” who are fighting back. “I would be lying if I said I didn’t have strong opinions on matters,” he told an interviewer last February. “I have biases, and I let them breathe. I don’t believe in denying them.”

That kind of narrative makes wealthy progressives swoon, but it’s largely false. In truth, the seafood industry is part of a broader market-driven effort that has raised global living standards and lifted literally billions out of poverty in the developing world. But an activist core, steeped in the decades-long crusade against commercial fishing pioneered by fringe groups like Greenpeace, have turned to labor issues as the latest in a series of albatrosses they hope to hang around the neck of a long-hated industry. Urbina is one of the more prominent foot soldiers of this anti-industry campaign.

As a result, his work is characterized by gross exaggeration and cherry-picking to smear seafood producers around the world with the misdeeds of a few bad actors. The millions of men and women who rely on fishery activity to provide for their families—the very people Urbina claims to speak for—are painted at worst as criminals and at best as fellow victims of imagined corporate greed. The kind of “greed” incidentally that revolutionized seafood from a coastal luxury and turned it into a healthy and affordable worldwide staple.

As we’ll see, there’s a whole lot more to the story than Urbina and co. would have you believe.

Pay-for-play journalism

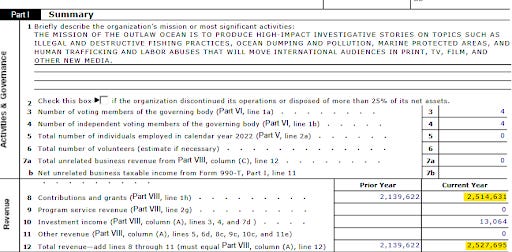

Like so many other journalists today, Urbina’s reporting isn’t so much financed by subscribers or advertisers as it is propped up by billionaire donors and the handful of “progressive” foundations they bankroll. These elites and the fellow-travelers they hire to staff their nonprofits view the media as a vehicle for advancing idiosyncratic and often wildly unpopular visions. To wit, Urbina’s nonprofit Outlaw Ocean Project, established in 2019, has received more than $1 million from wealthy donors such as Bloomberg Philanthropies, Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors, and the Carl Safina Center to push for luxury beliefs that would leave working people worse off.

All these Outlaw Ocean supporters belong to a tangled network of donors and activists who work tirelessly toward eliminating the seafood industry as it currently exists. They plant hit pieces on the salmon industry in the New York Times (and brag about it); they mislead consumers about antibiotics in seafood; and they lobby for restrictions on aquaculture operations that generate billions of dollars for the economies of developing countries like Chile.

Case study: Urbina’s slanted shrimp reporting

Urbina’s Outlaw Ocean Project behaves the same way, taking cash donations in exchange for slanted reporting.The organization recently published a series attacking India’s shrimp industry, curiously timed to coincide with an Associated Press investigation. Warning that the industry was a “growing goliath” Urbina’s story hung almost entirely on a single “whistleblower’s” testimony, but that didn’t stop him from accusing an entire national industry of mistreating its workers and lying to government regulators.

But the story changes radically when we include all the facts. Most importantly, the allegations leveled against Indian shrimp exporters collapse. The president of the Seafood Exporters Association of India (SEAI) explained why in a 2024 Firebreak piece rebutting the Associated Press‘s deeply misleading coverage:

“Nekkanti employees have the option to reside in dormitories at their facilities or can opt instead to commute, which many do. Nearly all have cell phones, ones that contain apps with direct hotlines to government agencies that oversee workplace safety. They routinely come and go from those premises as they wish, as Nekkanti’s documented entry and exit logs demonstrate.

Those logs are hard proof because the workers themselves sign in and out. Yes, there are guards on site but that is to protect employees and property, and to prevent unauthorized personnel from gaining entry in what can be dangerous areas. The safety and security of its workers is the primary concern of Nekkanti. Most importantly, in the years Nekkanti has provided those dormitories, not once has any employee filed a complaint that they were held against their will.”

These are not mere oversights or honest mistakes. We know that because the companies falsely accused of mistreating workers repeatedly tried to contact hostile reporters, in this case from the Associated Press, to set the record straight before these stories were published. Their outreach was ignored.

An opaquely sourced “report” from a group called the Corporate Accountability Lab (C.A.L.), which both the AP and Urbina cited as confirmation of the industry’s sins, was itself chock-full of errors. Crucially, the report made vague allegations about labor abuses and dangerous working conditions throughout India’s shrimping industry. But exactly which companies committed these abuses and where these awful conditions existed were never specified, as SEAI pointed out at the time. In fact, when SEAI provided evidence that these abuses did not occur on their members’ watch or in their state-of-the-art facilities, Outlaw Ocean still included C.A.L.'s speculation as key evidence in its reporting; four out of the five stories in Urbina’s series are built on the Corporate Accountability Lab report.

That Urbina’s own “reporting” was timed to coincide with the fallacious AP story, and that both are built on the same flawed C.A.L. report, reflects a common tactic: the use of different appendages of the same activist network to create the illusion of scale and consensus.

The job of journalists is to verify claims before repeating them, but in the new model of journalism as activism, the echo chamber is the point.

Urbina: a journalist exposed by other journalists

Urbina will no doubt pen more hollow “exposés” taking aim at the seafood industry. But his work has so thoroughly stretched the standards of ethical journalism that other reporters have taken notice. “Did a journalist get into the music business to help the oceans or help himself?” a New York Magazine headline asked in December 2021.

You see, when he’s not using his journalism as a weapon, Urbina doubles as an amateur musician, co-writing techno songs with garish titles like “Slow-Motion Mrder,” “Destroying The Commons,” and “The Sea is on Fire.” This discography, which Urbina released as the “Ocean Outlaw Music Project,” portrays humanity as an enemy of the planet. It features no lyrical content, save for sampled quotes from radicals and activists like Noam Chomsky, declaring that “the human species … is destroying …the Environment. It’s a common possession and we’re destroying it.”

Based on the testimony of artists who participated in the Outlaw Ocean Music Project, the 2,500-word New York mag story paints a troubling picture of Urbina as a self-aggrandizing hustler who hatched a scheme to take credit (and royalty payments) for music he didn’t write. “A plan to expand the reach of his journalism to a new audience,” the story noted.

Benn Jordan, one of the hundreds of musicians involved, described Urbina’s project as “a scam.” Looking back on the affair, NYMag observed that Jordan and others viewed Urbina as a conman who lured “musicians into onerous contracts under false pretenses, promising promotion and exposure that never materialized, and funneling music revenue into his own pockets.”

We certainly aren’t experts on the music business, but we do recognize an environmentalist huckster when we see one.