East Palestine In Perspective: Here's What Hysterical News Reports Got Wrong

News coverage of the East Palestine train derailment has ranged from hysteria to hysteria. One would think that one of the most dangerous chemicals in the world is being discharged from the train. Has anyone bothered to actually examine how toxic vinyl chloride is? You may be surprised.

Deadly toxin or just an average chemical?

The media has used predictable scare tactics in covering the East Palestine train derailment, subsequent fire, and release of vinyl chloride and its combustion products. A silly New York Times opinion piece, written by non-scientists, has gone as far as calling for vinyl chloride to be banned as if it's some chemical warfare agent. Unfortunately, media coverage has lacked perspective and this is at least partly responsible for the "end of the world" theme repeated over and over.

Has anyone even asked the following questions: How toxic is vinyl chloride? How does it compare to other chemicals? What are the realistic long-and-short consequences of the accident for people and the environment? Is it a chemical that should have ever been on that train in the first place?

To address these questions we need know to more about vinyl chloride’s chemical, toxicological, and carcinogenic properties. First, for some perspective, it is helpful to compare vinyl chloride to two familiar chemicals: chloroform and alcohol. When it comes to toxicity and carcinogenicity, the three have more in common than you might suspect. A valuable resource for doing so is a database of the comparative hazards or lists of chemicals from the National Fire Protection Association.

The National Fire Prevention Association Safety Diamond System

"The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) is a global self-funded nonprofit organization, established in 1896, devoted to eliminating death, injury, property and economic loss due to fire, electrical and related hazards."

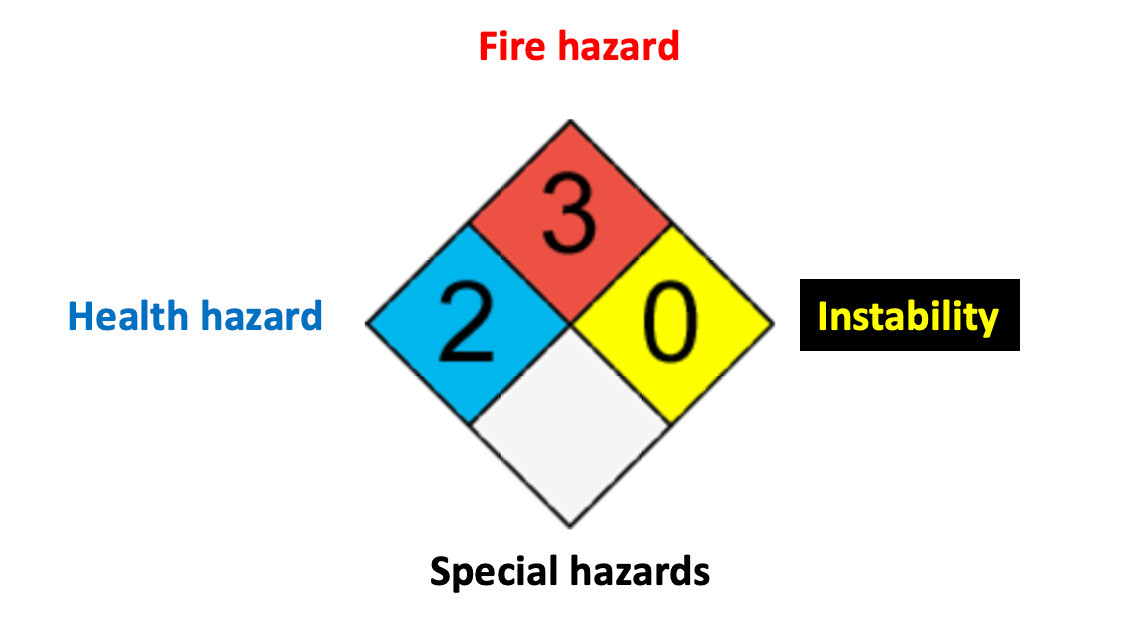

Among the many functions of the NFPA is the identification and evaluation of hazardous materials that first responders may encounter in case of a fire or spill. As such, the organization has a database of hundreds of potentially hazardous chemicals along with warnings about the particular hazards of each substance. As stated in the NFPA's disclaimer (1) the information provided is qualitative, not quantitative, and may have data gaps. Nonetheless, it is a useful tool for coping with accidents like the one in Ohio. Here's an example of an NFPA safety diamond.

NFPA diamonds provide advice about four types of hazards of hundreds of chemicals. The blue square represents health hazards and the red square flammability. For the purposes of this article instability (yellow square) – whether something will spontaneously explode (TNT is category 4) – and the white square (special conditions) are less relevant. I will focus only on health and flammability.

What do the numbers mean?

NPFA provides broad descriptions for five health categories. These are the numbers found in the blue square.

And for flammability:

Some examples that may surprise you

How deadly is vinyl chloride? Below are the safety diamonds for it plus chloroform, and ethanol. There is more similarity than you might expect. None of them are especially toxic, as indicated by their class 2 (blue square) status.

Here are two that are more toxic:

NFPA safety diamonds for alcohol, chloroform, and vinyl chloride. Additionally, NFPA safety diamond for nicotine and hydrogen cyanide.

Acute animal toxicity - LD50

Another method to evaluate chemical toxicity is involves laboratory animals. A common measure of chemical toxicity is the LD50 test, which determines the dose of a given chemical required to kill half the lab animals exposed to it, usually orally. It provides useful information on the toxicity of a given chemical but with certain limitations:

LD50 in lab animals provides only one data point – the acute (single dose) lethality of the chemical when given to lab animals, usually rats, by mouth. It does not address chronic exposure, long-term effects, or carcinogenicity. Furthermore, toxicity and metabolism in rats can be very different than that of humans. That said, LD50 does a good job of identifying very dangerous (or very safe) chemicals, especially if the pattern of toxicity is similar in other animals, such as mice, rabbits, guinea pigs, etc.

Table 1 shows LD50 values (the higher the number, the safer the chemical) of common substances.

Table 1. LD50 values of vinyl chloride compared to some common substances. The higher the number the safer the chemical. Keep in mind that exposure at the accident was from inhalation, not oral consumption, so these data are only indirectly applicable. It is difficult to determine inhalation toxicity from oral LD50 values. It is, at best, an approximation.

Bottom line: Vinyl chloride when given orally has very low toxicity in rats. Its toxicity is comparable to that of alcohol and much less so than widely-used OTC drugs. You will not find this in any news story.

Rats and humans: inhalation

Did people inhale enough vinyl chloride to be harmed? It's impossible to say but it would have taken quite a bit.

The acute toxicity (rat oral LD50 >4000 mg/kg; rat and mouse inhalation LC50 390,000 mg/m3 and 294,000 mg/m3 respectively) is low. Anesthetic effects have been reported in humans at levels of 12,000 ppm (30,720 mg/m3 for a five-minute exposure period.

Is 12,000 ppm a lot? Yes, it is. According to OSHA:

Action level means a concentration of vinyl chloride of 0.5 ppm averaged over an 8-hour work day.

That's quite a difference. Like chloroform, which was used for general anesthesia for more than 100 years, vinyl chloride elicits anesthesia-like effects at high doses - more than 20,000 times the levels that set off an alarm at OSHA. It is possible that it would have been a useful drug when general anesthesia was in its infancy.

What about cancer and other long-term effects?

Like chloroform and ethanol, vinyl chloride is classified as a carcinogen. But not from acute exposure. It is an occupational carcinogen, a chemical that can cause cancer (in this case liver cancer) as a result of long-time exposure. [Emphasis mine]

"Vinyl chloride monomer (VCM) is an IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer) group 1 carcinogen known to cause hepatic angiosarcoma (HAS) in highly exposed industrial workers."

The same holds true for other conditions that can arise from chronic, but not acute, exposure to the chemical:

"One-time acute exposures to VCM, causing mild symptoms such as dizziness and headaches, have not been proven to propagate long-term effects."

Source for both quotes: Vinyl Chloride Toxicity

This information should reassure people who were briefly exposed. Cancer from chemicals does not work this way; it takes a long period of exposure. I haven't seen any comparisons, but I'd bet my last penny that the cancer risk from smoking absolutely dwarfs that of a single exposure to vinyl chloride, no matter the dose.

And drinking too. A Lancet Oncology paper estimated that more than 700,000 cases of cancer - about 4% of total new cancers - are from drinking.

Even if I lived near East Palestine I would not be concerned about liver cancer from such short exposure. But I might stop drinking. Alcohol, upon ingestion, forms acetaldehyde, which is both toxic and carcinogenic

Burning – the big problem

This is where the difference between vinyl chloride and alcohol becomes apparent. Different chemicals form different combustion products. Obviously, automobile exhaust doesn't pose an acute threat or everyone on the Cross Bronx Expressway would be dead. But the same cannot be said for vinyl chloride. Its combustion products are anything but benign. A partial list:

Phosgene (a deadly respiration toxin) was used in WWI as a chemical weapon

Hydrogen chloride (a severe irritant to the eyes, skin, nasal passages, and lungs). It is likely that the symptoms that residents experienced were from this. At very high concentrations HCl can be fatal but you would know it was present long before it would reach lethal levels. It is very unpleasant to get even a whiff.

Exposure to phosgene gas represents the most dangerous scenario and it isn’t clear whether this has been an issue. This remains the most troubling unknown scenario in the accident. Fortunately, these gases dissipate rapidly.

Of the gases emitted from burning, it is most likely that hydrogen chloride did the most damage, possibly being responsible for the death of fish and animals in the area. Fish are very sensitive to acidic (low pH) water (but not so much to vinyl chloride). It was probably the hydrogen chloride that harmed fish, pets, and other animals. Unless you've taken a snootful of the stuff, something I inadvertently did many times during my career in the lab, you cannot fully appreciate what an unpleasant experience that is, but it is not a deadly toxin like phosgene. My best guess is that after almost four weeks very serious disease would have become evident if phosgene were present in significant quantities.

How bad was this accident?

No one wants to host a burning train full of chemicals, but as far as poisons go, there are far worse chemicals that are regularly being transported around the US. Here are some:

Methyl isocyanate, a deadly poison that was responsible for more than 10,000 deaths in Bhopal, India in 1984 following a leak.

Anhydrous ammonia was released in a truck accident in Texas in 1976. Five people died from inhaling it. Hundreds were hospitalized.

Ammonium nitrate, an explosive fertilizer, destroyed an entire city in 1947 killing 600 people. This is just one of many accidents from the chemical.

Concentrated sulfuric acid will destroy all living matter, including human skin. And if mixed with water a violent explosion can result.

What about the environment?

To the extent that one can be "lucky" living near a burning train full of chemicals, vinyl chloride's properties make long-term environmental problems unlikely. Why? Because vinyl chloride is a gas at room temperate and evaporates very rapidly. It is essentially the exact opposite of the case of PCB contamination of the Hudson River. Once PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) get into a waterway they are going to be there forever unless the contaminated river bed is removed. Not only is this group of chemicals non-biodegradable but also non-volatile. The boiling point for the PCB class of chemicals ranges from about 500-700oF – not too different from the temperature of Venus.

Conversely, the boiling point of vinyl chloride is 8oF, so except under extraordinary circumstances, it's a volatile gas and evaporates rapidly. This makes environmental accumulation very unlikely. In fact, an EPA report estimates that the half-life (the amount of time it takes for half of the chemical to be cleared) from soil and water is very short:

"If vinyl chloride is released to soil, it will be subject to rapid volatilization with reported half-lives of 0.2 and 0.5 days...If released to water, vinyl chloride will rapidly evaporate... [with] a half-life of 0.805 hr."

So, after 5 half-lives (using the value 0.35 days for the half-life) 97% of the chemical will be gone from soil. In water, most will be gone in a few hours. The fate of the chemical, should it find its way to groundwater is not well understood:

"Vinyl chloride will be expected to be highly mobile in soil and it may leach to the groundwater. It may be subject to biodegradation under anaerobic conditions such as exists in flooded soil and groundwater.

Bottom line

This accident could have been much worse.

The train didn't explode. This would have created immense damage, including more deadly combustion products.

Vinyl chloride, news reports notwithstanding, is a relatively benign chemical in terms of its inherent toxicity, much less toxic than some of the truly deadly poisons that are routinely transported around the country. Some of these would have created a disaster with the loss of human life.

The chance of cancer arising from a single exposure to vinyl chloride is vanishingly small.

The media is spreading hysteria because that's what they do.

A train carrying chemicals engulfed in flames is scary enough. We don't need the extra decoration.

This article was originally published at the American Council on Science and Health.