Are There Too Many Scientists?

Are Fear Campaigns Fueled by the Bitter Under-Employed?

We often hear NGO activists telling us that we need to listen to “the” science or respect the evidence in highly-charged policy debate from pesticides to processed foods to climate to vaping. The Firebreak recently saw how groups like the Environmental Working Group or the Heartland Health Research Alliance are publishing papers on their campaigns that they claim as definitive science. But who really is the scientist and what is scientific?

There are many different sciences, degrees of academic standards and levels of quality among scientists. The term “the science” is used by people who don’t really have an understanding of the scientific method and think of science as a means to an end – a tick-box.

There are too many scientists today and with limited opportunities, the profession is ripe for exploitation. Today there are six times more scientific and engineering doctorates awarded than in the 1960s, when the last main academic expansion took place.

So where do all of these PhDs go?

Over the last 35 years, working in industry, the academe and regulatory organizations, I’ve noticed a marked scientist employment trend.

Outside of the medical field, the brightest scientific minds are often poached by industries and companies before they even defend their theses. Companies pay top dollar and are constantly searching to recruit the most innovative minds via internships and fellowships. Billions are spent in corporate research centers to ensure the best minds, using the best technologies can find the best innovative solutions. It is ironic that these scientists are often restricted in what they can publish because of how their industry affiliation has somehow blacklisted them. Their research data is not allowed to be considered in risk assessments in organizations from the European Commission to UN agencies.

Those scientists who are not fêted as the belles at the ball tend to hang around in universities, trying to get published and relentlessly networking at conferences. Those with good people skills can get on a lecture/professor track (particularly if they are not white males) while others follow a research track. If they have a network and they are lucky, they could move into research agencies or government institutions, but after a few years, the political nature of the beast often leaves them cynical or petty (usually both).

This still leaves a large amount of the scientific community unaccounted for. Many bounce around from post-doc to post-doc looking for a stable job but the most they can usually get is two to three years of funding. If one looks at open competition grant applications, the scholars are usually in their mid-30s, hoping for three more years of funding and willing to move to wherever the funding leads them. I often wonder how bitter they must feel when they see their former college classmates working in corporate research centers, well-paid, settled and with considerable research budgets. It is also frustrating for the schools trying to manage a large number of post-docs on limited career paths. Within the EU’s Marie Curie fellowship funding strategy, for example, there are programs to try to cross-fertilize researchers with non-academic partners.

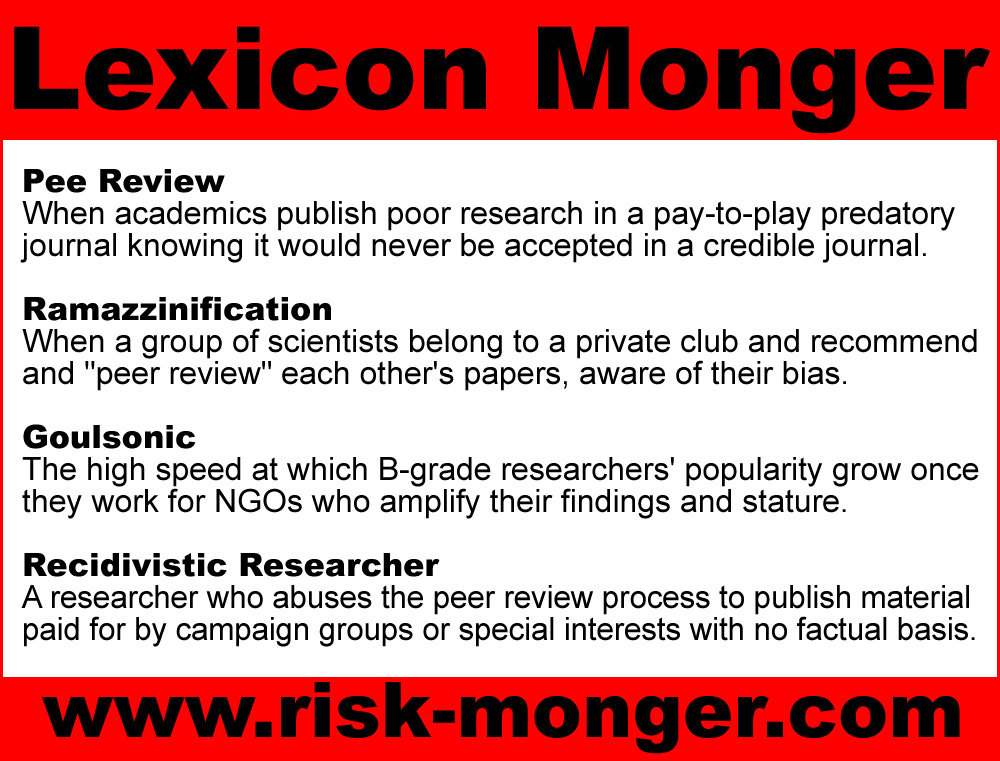

Then there are the last group of scientists who were more political on campus than academic. Their research skills lacked and they rarely stood out. They often hung around the activist professors who spoke out strongly on political issues and were often quite contentious with the main research community. As post-docs, they were dependent on their guru obtaining funding, and if that dried up, they were left on their own. When much of the dioxins or endocrine disruption research funding ran out in the mid-to-late-2000s, for example, there was an entire class of post-docs that had to scramble to find another issue. Many crossed over into pesticide fields and suddenly started touting themselves as “glyphosate experts”.

Being bitter, unemployed and middle-aged, this last group of scientists were vulnerable to exploitation by activist groups looking for PhDs to give their campaigns credibility. And the activist communications machine gave them attention, turning people like Dave Goulson, Chuck Benbrook or Alexis Temkin into media darlings. As long as their scientific results amplified the NGO campaigns, they would stay at the center of the activists’ attention.

Until the early 2000s, there was not enough opportunity to absorb the excess scientists. But in the last two decades a new funding source has entered to compete with industry investment, government grants and regulatory positions. Foundations now are providing more funds to mop up these bitter activist scientists, giving them the means to publish their NGO campaign-driven papers, hold conferences with other activists and even fund scientific allies to join them in their “research”.

While their political persuasion led them to attack industry-funded research, these activists also had no respect for their former classmates now working in regulatory agencies, arguing that they were merely doing industry’s bidding. As truly independent scientists, these activists felt that only their work should be given attention. (…although they looked away when their foundation funding came from dark, donor-advised interest groups like the organic food industry lobby or tort law firms).

Pee Review

At the time of the rise of the mediocre activist scientist, the nature of academic publishing evolved with pay-to-play, predatory journals proliferating. These online journals can publish as many articles as they want and it does not matter if no one actually reads them. The “Sokal Squared” hoax showed how easy it was to publish gibberish in academic journals.

Not a day goes by when some obscure journal publishes a paper whose only worth is the author’s ability to pay the $3000 peer review fee and recommend three friends to review it. The only value of such poor science cloaked in scholarly fluff is for some NGO to coincidentally use it for a campaign or for some tort lawyer to cite it in an opening argument. NGOs like the Environmental Working Group or US Right to Know now have pages to promote their academic work, all second-rate research in low-level journals and all funded by dark, anonymous, donor-advised funds.

With so many scientists now finding new employers, funding and easy publication sources, the NGOs now claim to be the trusted scientific source. But what they are claiming to be “the” science and the reliable, untainted research, is creating unnecessary fears of chemicals, food additives, plastics exposures, pesticides, vaping, nuclear and, well, whatever they are paid to publish on.

The media does not understand the situation or get how the weakest scientists publishing poor research in fraudulent journals is all part of the NGO campaign game. They bought into the “industry science is corrupt” message and the “don’t trust the regulatory scientists” lines so, by default, the activist science is what is peddled to the public.

The next time you read some media article about “the” science that is tied to an NGO campaign, dig a little deeper. Look at the name of the journal, the funding and the time it took from submission to publication. There are a lot of scientists out there, but not all of them are honest, unbiased or, well, very good.

And remember, the brightest minds of science, the ones recruited by industry before they had graduated, have been ostracized by this publishing-policy nexus. Bitterness abounds.