Why Have Health Leaders Rejected Vaping?

Tobacco Harm Reduction Health Strategies are being Ignored, Costing Lives and Increasing Suffering (Part 2 of a Three-Part Series on Harm Reduction)

The first part of this three-part series demonstrated how health leaders had abdicated responsibility to tobacco harm reduction strategies. Rather than accepting the positive relative risk profile of nicotine alternatives like vaping, snus or nicotine patches, scientists involved with the WHO have conflated these smoking alternatives with tobacco. The only health leaders in this debate, the pro-vaping advocacy groups are small, under-funded and facing a wall of NGOs, foundations and policy activists who have stigmatized them and the products they are struggling to keep on the market. This second part will consider why the health authorities have rejected harm reduction strategies in this case and the consequences for health policies.

What are some of the policy handcuffs or prejudices that have led to the lamentable policy decisions that have prevented a wider use of e-cigarettes over smoking tobacco and stigmatized reduced harm strategies in general?

Righteous Risks (Prohibitionists)

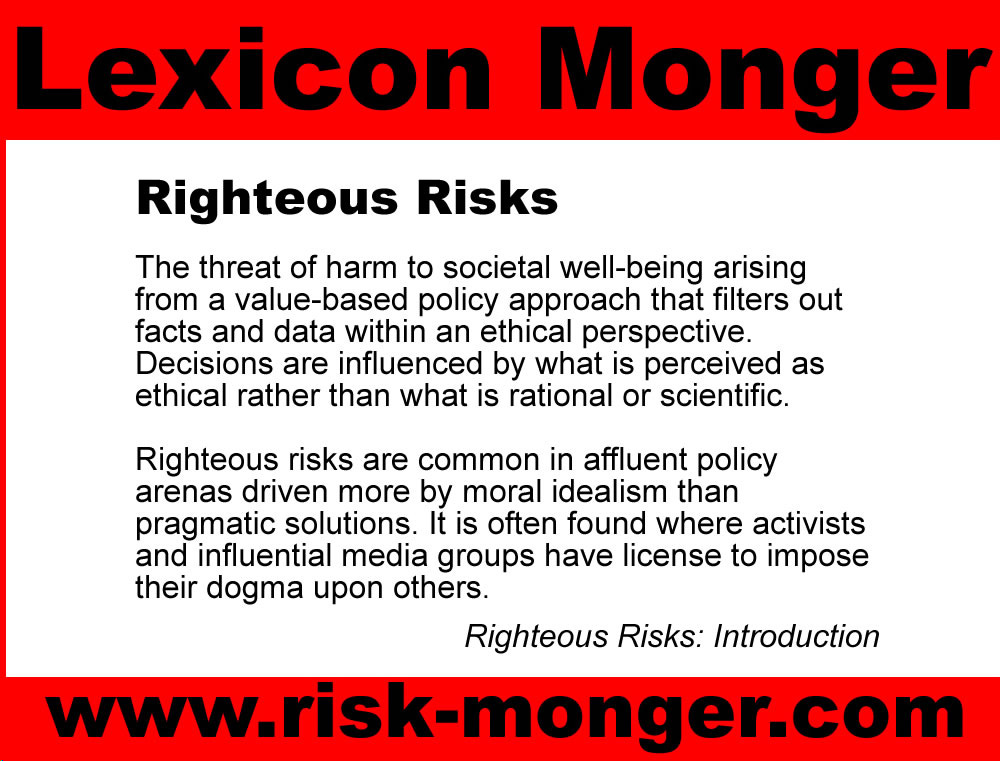

Several years back, I wrote a series on the difficulties of managing righteous risks. A righteous risk is any exposure to a moral or value-based hazard which has no factual or evidential foundations. Policymakers react to an indignant or morally-outraged population in often irrational manners, accepting blatant inconsistencies, contradictions or hypocrisies in policy implementation, often without any public opposition or enforcement of regulations or best practices. When health zealots lead public policy, as is presently the case in the United States with the MAHA movement rushing to redefine health policies, individual rights and freedoms are easily trampled on.

The prohibition movement in the US in the 1920s was a good example of how righteous regulatory behavior can create negative health consequences. Rather than a blanket ban on all alcohol, if leaders had imposed a reduced harm strategy (with reasonable regulations monitoring the production, sale and levels of alcohol), none of the societal damage and human loss (from poisonous bootleg to gangster-run black markets) would have taken place. Now health activists are campaigning for a prohibition or banning of all nicotine products. The difference today is that these groups have more money than the churches and women’s groups of the 1920s.

Anti-industry Bias

The shunning of the reduced harm strategy on vaping alternatives is really quite extraordinary when considered in light of the recent trend to decriminalize or legalize the sale of cannabis products. Cannabis normalization is clearly a reduced harm strategy (controlling product safety and ingredients, reducing black markets and organized crime, normalizing the use of a safer leisure drug…). It should trigger the same reaction as those fighting against the reduced harm nicotine strategy: it is a gateway product, addictive, health consequences… But instead, the same health advocates campaigning against nicotine are championing cannabis legalization.

At the moment, most dispensaries and growers are small-scale, local operations. If a company like Philip Morris were to enter the cannabis market, would the health activist community have the same attitude? It seems that the outrage against reduced harm use of nicotine products has more to do with the role of industry and the presence of Big Tobacco on the vaping market.

There were three strikes against Big Tobacco that will never be forgotten nor forgiven. 1) It is an industry driven by profits and exploitation (of markets, people, the environment…); 2) Certain actors in this industry have been caught lying to advance their business opportunities; and 3) The marketing objectives of this industry has been to focus on promoting an addictive behavior on children and vulnerable individuals.

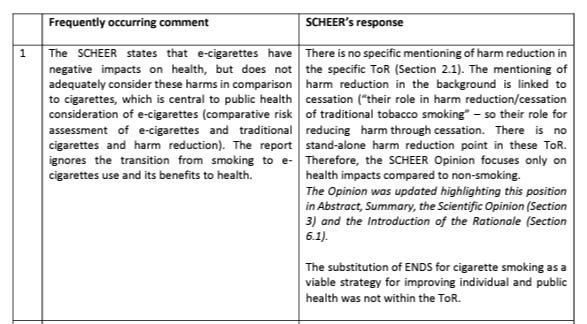

The small activist group of health zealots associated with a Lancet project are now trying to tobacconize all other industries (from food and drink to chemicals to Big Pharma) via the World Health Organization’s Commercial Determinants of Health strategy. Corporate leaders from other industries have to stop behaving like the second slowest zebra and had better start embracing harm reduction as an existential strategy.

Stigmatizing Vaping with Tobacco

“Vaping is smoking and smoking is vaping … tobacco and nicotine are the same and need to be controlled in the same way.” This seems to be the strategy behind all health policy advice on non-tobacco nicotine alternatives coming from the WHO, the large number of anti-tobacco NGOs and activist foundations like Bloomberg Philanthropies. Their goal is to prevent vaping from becoming a more popular smoking cessation strategy, so they have imposed blanket stigmatizations like restrictions on vaping indoors or in confined spaces, flavor bans and marketing.

The lack of science or intelligent reasoning here is stunning. How can second-hand vapor pose any risk to others when the initial risks are extremely small? The activists only objective here is to keep tobacco harm reduction tools sealed in the tobacco box, ostracize vapers and restrict use. These spiteful old tobacco warriors don’t care if millions more smokers struggle to quit, and suffer worse health consequences.

Sadly, because the vaping community is so small, they have been unable to fight the ignorant policy decisions these activists have pushed through. The anti-tobacco / anti-nicotine lobby needs to be broken up, their funders need to be highlighted and stigmatized.

The Absolutist / Perfect World Approach

There has been a trend to zero risk over the last two decades with the regulatory lexicon peppered with expressions like zero waste, net zero carbon emissions, zero plastics … In the health domain, this has manifested itself via the a risk-averse population’s demand for policies that guarantee that a product is safe (with certainty).

Safety and certainty though are emotional concepts that mean different things to different people. By foolishly adopting these concepts in some absolutist terms, policymakers have willingly handcuffed themselves. Under such restrictive language, reduced harm is still harm (no matter how small) and thus not a useful policy alternative. Because safe and certain don’t actually exist, the best regulators can do is impose precaution.

The precautionary principle demands that for a product, substance or activity to be approved, it must be proven (with certainty) to be safe. If this standard were to be applied without prejudice, then all products would have to be taken off of the market, but instead, precaution is imposed only when there are issues that activists have been campaigning against (chemicals, pesticides, food additives…).

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, when there was a great amount of uncertainty of the risks from the emerging coronavirus, governments imposed precautionary lockdowns on their populations (until it was deemed to be safe for the public to interact again). There was no risk management strategy in place (precaution is uncertainty management), and at a certain point, with public outrage against the lockdowns building, the 100% safe policy was reduced to a more rational approach of reducing exposure to hazards to as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA – the key to risk management).

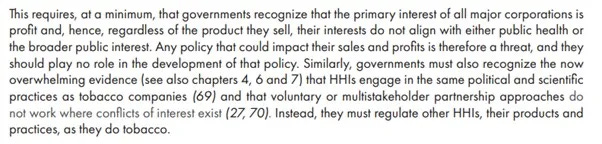

This 100% safe strategy is regularly applied in Europe. When the European Commission asked their Scientific Committee on Health, Environmental and Emerging Risks (SCHEER) to assess the safety of e-cigarettes, it only asked them to compare the risks of vaping against not smoking at all (rather than comparing the risks to smoking tobacco products). To little surprise, vaping was found to be less safe than those who never smoked nor vaped.

In the real world though, people understand that vaping is safer than combustible tobacco. In the real world, people understand that nothing is 100% safe. In the real world, people are reasonable and not driven by political bias. Even the scientists on the SCHEER committee know that.

Addiction fears

Like the opioid debate in the US, addiction experts rather than public health experts are advising regulators on vaping policies. If nicotine is addictive, then it is seen as a harm regardless of the level of reduced risk compared to tobacco. For anti-addiction campaigners, harm is harm that demands zero tolerance. For anti-alcoholism campaigners, for example, the saying goes: One drink is too many and a thousand is not enough.

But are all addictive substances the same and should we stop such behavior without reflection? When does an addiction become identified as an addiction? When it becomes a problem (to one’s health or to those around them)? When it becomes a dependence? As a boomer, I wonder now if I am becoming addicted to my mobile phone. How much more must Gen Z phone addicts be “suffering”?

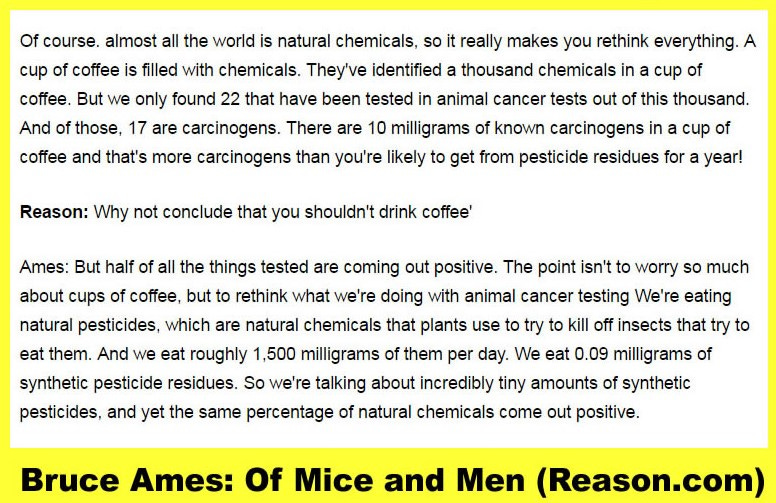

Caffeine is addictive (and for some, with greater negative consequences than nicotine) but I don’t see the same groundswell of activism to ban coffee. Coffee is promoted as the “new sexy” in the media, films and socializing. Perhaps regulators should take advantage of this trend and start taxing your morning brew to curb addiction (and raise revenue). Nicotine is not a carcinogen nor does it contribute to cardiovascular disease. Can the same be said about the 1000 plus chemicals in my cup of coffee?

As a person with osteoarthritis, suffering chronic pain, I take issue with people who live pain-free telling me I had better not take painkillers to help me through the flares and dark days because they could “create an addiction”. Let me choose to manage the risks vs the benefits of effective pain management treatment. I class such smarmy activists with the affluent environmentalists who tell me I need to buy organic food or source renewable energy. Of course they don’t stop at lecturing me, they want to change regulations to stop people like me from having a choice.

Zealots are addicted to prescribing their virtues on others but I don’t see anyone trying to treat them as a disease.

The regulatory restrictions on tobacco harm reduction alternatives is pure madness. Rather than promoting policies to help smokers quit an unhealthy habit, save lives and reduce the healthcare burden, they are imposing more restrictions, stigmatizing vapers and deliberately producing bad science to feed into a well-funded anti-nicotine activist network. Part 3 of this series on the rejection of harm reduction as a health strategy will focus on the source of the madness: the World Health Organization and the funders behind them.