Why NGOs like Greenpeace No Longer Really Matter

The Energy Transfer Court Victory Shows How NGOs Have Become Feeble

Last week a North Dakota court verdict ruled against Greenpeace USA with a jury awarding $660 million to Energy Transfer LP for the physical and reputational damages from the 2016-17 protests at the Dakota Access Pipeline facilities near Standing Rock, North Dakota. Greenpeace will, of course, appeal and play out all sorts of legal tactics (that they usually attack industry for doing). Or the activists will simply let the NGO fail and reconstitute themselves with a slightly different name.

But the scale of the decision got me thinking: What would an activist campaign world without Greenpeace or other large environmental NGOs look like?

Quite frankly, nothing would change. 50 years after their entry as an important environmental movement, Greenpeace has become a spent force. Activist campaigns have moved on and the five-decade-old NGO model has withered on the vine.

Evolutions in NGOs

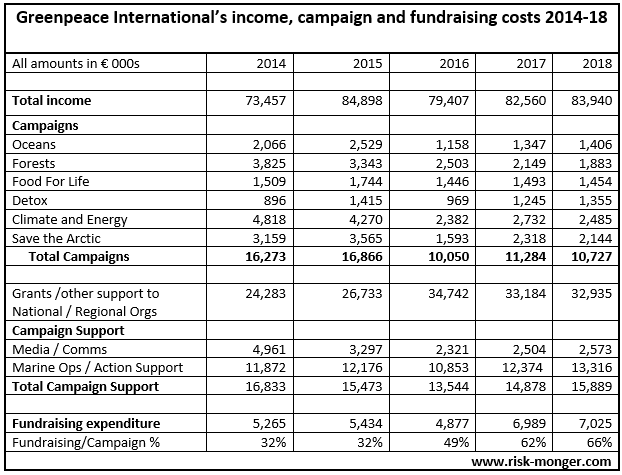

Prior to COVID-19, the activist world was already rapidly changing. The Greenpeace fundraising model was struggling to cover the costs per donation. They were spending more on overhead than campaign programs (see table below) with only a few regions earning enough to support the global network. The organization was struggling to manage a coherent strategy with extremists and moderates tugging policies in all directions. With internal dissent often boiling over, Greenpeace was unable to unburden itself from unpopular legacy campaigns against Golden Rice and nuclear energy. Their costs of running a naval fleet of aging ships became ridiculous and pointless.

At the same time the world of activism was changing. Campaign populism and individual activism was more immediate and impactful. While the Internet propelled Greenpeace, among other NGOs, to the roles of influential policy stakeholders in the early 2000s, they failed to tap into the communications shift to local social media communities, leaving the group out of touch and overburdened with the intricacies of regulatory policy issues.

When a media sensation like Greta Thunberg started to impact the climate debate in 2019 with her simplistic slogans, she did not ask to become a member of an NGO. Her voice became more powerful than the then bureaucratic Greenpeace.

At the same time, movements like Extinction Rebellion redefined how an activist campaign was to be managed: decentralized and light. The claim of XR founders like Roger Hallam was that the NGOs had failed and it was time for a grassroots movement to take over the climate crisis campaign. As the leaderless protest campaign began to block cities and dominate the media, several Extinction Rebellion founders met with Greenpeace directors in London and concluded the legacy NGO could offer nothing useful to the climate debate.

Environmental campaigning and societal impact had moved away from the once mighty Greenpeace, as it has for other groups like Friends of the Earth, WWF and EWG. Then someone coughed in Wuhan and the activist model shifted even more.

Foundations: The Shadow Actors

In the explosive climate campaigns of 2018-19, little was known about the roles of foundations pulling the strings behind the scenes.

The media thought little Greta just got on a yacht to sail the Atlantic by herself or show up at Davos to speak the truth. They did not see groups like the PR unit of the European Climate Foundation (a discrete fiscal sponsor that takes in over a quarter of a billion euros per year from foundations) managing the Swedish teenager.

When an army of small NGOs managed to landlock the Canadian province of Alberta from exporting its oil and gas, it took a government inquiry to reveal the extent to which billionaire-led foundations were directing the campaign from the shadows.

The Firebreak has been investigating why the media has not reported on the backroom foundation involvement. This mainly has to do with the news organizations and journalists themselves being funded by the philanthropists, often acting in collusion with special interest groups via dark, donor-advised funds.

Greenpeace USA has received funding from foundations like Rockefeller Brothers, Packard, Merck and Hewlett, but given the heavy bureaucratic baggage, political infighting and intransigence inside the NGO, it proved much easier and cost effective for the foundations to work with fiscal sponsors to create their own campaign organizations.

A Campaign Front Group

Why didn’t the Energy Transfer lawyers just sue the Rockefeller Brothers foundation instead of Greenpeace? If the Albertan government Allan Inquiry taught us anything, they were likely the ones pulling the strings behind the scenes at Standing Rock. It seems that NGOs like Greenpeace are just acting as front groups for the real campaigns going on below the surface. A similar situation can be seen in the anti-salmon campaign in Chile, where a lone Greenpeace protestor shows up in a boat near a salmon pen, attracting media attention, while the real impact is coordinated by a little-known fiscal sponsor.

How long before the foundations will no longer benefit from the cover and subterfuge provided by legacy NGOs like Greenpeace? How long before these foundations will have to come out into the open?

Did the lawyers, knowing full well that the Standing Rock funders were the foundations, reach an understanding with the billionaires? Perhaps a jury would not have come down as harshly on a charity, trust or foundation (generally perceived to be philanthropic and angelic compared to a widely reviled activist NGO).

Perhaps the Rockefeller Brothers foundation could afford better defense attorneys.

Shooting Bambi

The optics for the NGOs are perfect. Big bad industry is suing poor environmentalist hippies who were only fighting to save the world for us and our future generations. The message is that what industry wants is to put NGOs out of business (although ironically, that is precisely what Greenpeace wants to do to industry). The optical illusion is even stronger when another set of victims, the Native American tribes, are also brought in.

Industry’s reputation will not improve if the lawsuit continues being portrayed as an assault on Bambi.

The Greenpeace groups and campaigners listed in the lawsuit, like former Greenpeace USA executive director, Annie Leonard, are actually highly-paid corporate managers and politically connected operatives. They haven’t flown coach for decades. The Native American tribes, like the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, are fed up with Greenpeace trying to take the credit and lead on their Standing Rock campaign.

It should not go unmentioned that the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, in leading the actual protests, also takes in foundation funding to fight big oil. But Energy Transfer’s lawyers wisely chose not to take any tribes to court. Let the loud environmental activists take the fall.

Regardless the role of the Native American tribes, the reality is that Greenpeace got caught breaking the law, willfully harming and obstructing a company legally carrying out its business and destroying property. The charges fell under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), with the lawyers asserting that Greenpeace deliberately disseminated false and misleading information to incite fear, disrupt operations, and inflict economic harm. A jury looked at all of the evidence and determined a fair settlement. Greenpeace can and should pay the $660 million.

But instead, the NGO will continue to pretend they are some small, idyllic group of barefoot tree huggers dancing as the sun rises without a penny to their name. Maybe the Energy Transfer lawyers should freeze the Rockefeller Brothers’ assets as well.

If NGOs continue to keep up the façade of bit players and underdogs in the stakeholder debates, barely able to afford an office or staff, while foundations continue to pump hundreds of millions into fiscal sponsors who construct astroturf organizations to run the actual campaigns, then groups like Greenpeace need to be identified for what the have become: mere tokens. They will be there on the surface, like a policy pantomime, pretending to represent stakeholders while the real campaigns and lobbying are conducted under the radar by other, non-transparent groups with the serious foundation capital and further dark, special interest funding.

With NGOs becoming a spent, tokenized force, maybe it is time to start suing the foundations.