The European Climate Foundation's Dark Net-Zero Flotilla

Part 2/5: How the European Climate Foundation Bought Brussels

The European Climate Foundation (ECF) has dominated the climate debate in Europe and globally by funding environmental NGOs, using them like an “influence flotilla” to forward the agenda of large climate-driven foundations pulling the strings behind the scenes. The Firebreak has been conducting an ex-post evaluation on how the climate/net zero/ESG/WEF agenda over the last decade had almost succeeded in dismantling Western economic and political structures, and how a group of billionaires have been acting as a new power base, using their foundations to influence the media, politicians and NGOs. This translation of Florence Autret’s article, published in 2023, fits nicely within this objective. Her analysis is precise and insightful. For the purpose of considering each of the valuable points of her argument, the English translation has been broken into the following five chapters:

______

While the European Climate Foundation hardly communicates with the public, it is, however, well-integrated into the headquarters of the European executive. In 2015-2016 (the year of and following the Paris COP Climate Agreement), ECF representatives were received no less than 47 times by European commissioners and/or members of their offices. That is an average of twice a month, which places the European Climate Foundation among the top lobbies that most frequent the Berlaymont, the headquarters of the European Commission. This does not include the meetings of the NGO coalitions that are most closely linked to it.

Shortly before COP24 in Katowice, Poland in 2018, another phase of intense lobbying preceded the European Union’s publication of the first document that included the objective of carbon neutrality in the extension of the Paris Agreement.

This EU communication, entitled “A Clean Planet for All”, was presented by Miguel Arias Cañete, then Commissioner for Climate Action and Energy, and prepared by DG Climate, headed by Mauro Petriccione. The European Commission report closely resembles a document published a few weeks earlier by the ECF under the title “Net Zero 2050”, from which the European Commission adopts their scenarios.

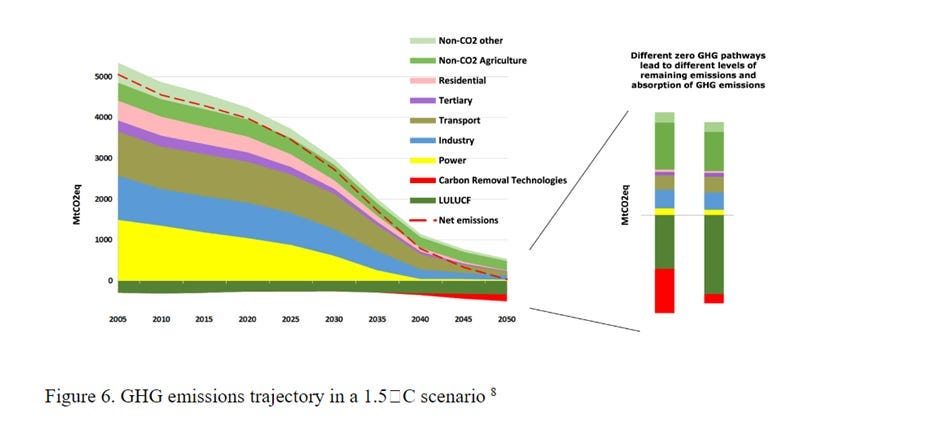

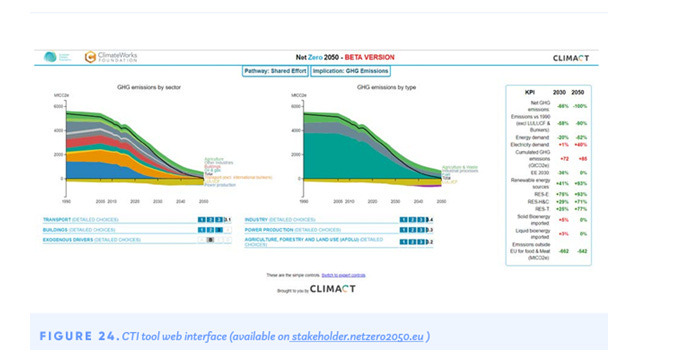

The European Commission document also includes, unsourced, a graph identical to the one in the appendix to the ECF report. It indicates the trajectory of emissions reduction by sector (agriculture, housing, transport, etc.) to get to “Net Zero in 2050”, including “negative emissions” produced by CO2 storage techniques and its sequestration in soils (LULUCFs - standing for land use, land-use change and forestry).

Mobilizing the Mayors

In the autumn of 2018, as climate protests began to gain momentum around the world, Eurocities, an association representing more than 200 European cities, began promoting “Net Zero in 2050” and launched the “Climate Action Call”. Eurocities had a lobbying budget of €1.25 to €1.5 million in 2022 and 12 people accredited to institutions, but does not disclose its sources of funding from outside the EU (around €500,000).

Eurocities communication was gaining momentum, at the very moment when hundreds of thousands of young people were marching in these same cities and their muse, Greta Thunberg, was touring the capitals to denounce the inaction of political leaders. The Swedish activist was received at the Elysée by Emmanuel Macron on February 22, 2019.

On May 7, two days before an “informal summit dedicated to the future of the EU” held in Romania, Eurocities was back at it. “The mayors of 210 cities representing 62 million citizens call on the European Council to agree on a path to net zero emissions by 2050,” tweets this organization, which at this time had an impressive staff of 78 people.

“A new climate ambition”

French President, Emmanuel Macron, saw the opportunity.

In December 2017, Macron brought together the elite of business and philanthropy worlds at the Elysée Palace for the “One Planet Summit”, all gathered around the president of the ECF (photo).

In the spring of 2019, a few weeks before the European elections, Macron displayed his priority for a “new climate ambition”. At the end of this informal Council, he appeared alongside the Dutch and Luxembourg Prime Ministers, Mark Rutte and Xavier Bettel, discussing with young activists to whom Bettel assured that the subject of climate change had indeed been debated behind closed doors between “leaders”.

Three years later, Macron wrote on Twitter about this meeting:

With the 2019 European elections over, “Net Zero” became the mantra of the new Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, who spoke about it in her first speech to Parliament. It would be the central axis of the “climate law” and the Green Deal strategy presented in 2020.

From Gazprom to Greta

In 2021, the Politico.eu website published one of the rare journalistic investigations into the ECF or, more precisely, an extension of the ECF: the “Global Strategic Communications Council” (GSCC). The article’s subtitle: “After all, someone’s gotta check Greta Thunberg’s emails”.

The GSCC now presents itself as a “international, collaborative network of communications professionals in the fields of climate, energy and nature”, according to its website. But at the time of the Politico investigation, the organization was still almost clandestine.

Against the climate-skeptic discourse, an army of GSCC spin doctors borrowed their “PR” (public relations) techniques from multinationals. Their boss, Tom Brookes, joined the ECF in 2009 after working for Microsoft and Apple, and after having co-founded the lobbying agency, GPlus. One of the success stories of European lobbying, GPlus was created by former Commission spokespersons and journalists (including Brookes), who notably made a killing by providing public relations for the Russian gas group, Gazprom, in Brussels in the 2000s.

If Brookes came out of the shadows, for once, to speak “on the record” to Politico, it was because the newspaper had some embarrassing information gathered by chance during a bus ride in Brussels. A journalist from the editorial office overheard a phone conversation between a GSCC employee and we don’t know who. What he heard was interesting enough for the site to decide to dig deeper.

To help decipher it, Politico turned to an academic, a specialist in climate philanthropy. Edouard Morena has studied the making of international climate agreements for years. Regarding the way in which NGO communications is organized, he speaks of a “flotilla approach”.

“Not everyone is under the same brand, but everyone is pushing their own brand in the same direction,” he told Politico.

Politico took nearly six months to publish its investigation. It did not say who the protagonists of the conversation that triggered it were. However, Politico did slightly lift the veil on its strange influence techniques. On the GSCC, “It’s by far the best source of intelligence at the COP meetings,” said a former reporter. “It’s like the door to Narnia… You don’t know it’s there until you know it’s there.”

After the Politico publication, the “GSCC network” would reveal details about its staff and funders on its website. It is presented there as “a collaborative project hosted by the European Climate Foundation.” The five foundations that fund the GSCC are all part of the ECF’s funding round. For a long time, an ECF press officer would indifferently sign his emails “communication advisor” from one or the other. Tom Brookes, ECF’s executive director of strategic communications at the time of publication, is now CEO of GSCC, while remaining an ECF fellow.

The Politico article was a brief ray of light in a sea of opacity.