The ECF Network of Foundation Funders

Part 5/5: Why did American Foundations create a European “Little Sister”?

The European Climate Foundation (ECF) has dominated the climate debate in Europe and globally by funding environmental NGOs, using them like an “influence flotilla” to forward the agenda of large climate-driven foundations pulling the strings behind the scenes. The Firebreak has been conducting an ex-post evaluation on how the climate/net zero/ESG/WEF agenda over the last decade had almost succeeded in dismantling Western economic and political structures, and how a group of billionaires have been acting as a new power base, using their foundations to influence the media, politicians and NGOs. This translation of Florence Autret’s article, published in 2023, fits nicely within this objective. Her analysis is precise and insightful. For the purpose of considering each of the valuable points of her argument, the English translation has been broken into the following five chapters:

Part 2: The European Climate Foundation's Dark Net-Zero Flotilla

Part 4: How the finance industry found a way to save itself: Nature

_________

Laying out the financing network and decision-making circuits of this climate ecosystem is all the more difficult since the ECF often intervenes alongside foundations that finance it and/or the Climate Works Foundation (CW), created at the same time, in California, partly by the same large foundations. The Climate Works Foundation also sends significant sums to its European “little sister”.

Like a trust whose capital providers are never seen, ECF and CW act as a screen between the public and the philanthropists who created them.

These philanthropists include:

Michael Bloomberg, founder of the financial information group and foundation named after him, former mayor of New York and candidate for the Democratic candidacy in the US presidential elections in 2020. He was also appointed in 2021 as “United Nations Special Envoy for Climate Ambition and Solutions”

the family of the founders of Velux (KR Foundation)

the family of Alan Parker, founder of the Oak Foundation (which does not communicate any financial data). Parker became a billionaire thanks to the proceeds of the sale of his shares in a chain of duty-free stores to LVMH.

the McBall MacBain couple who created their foundation in Switzerland after the sale of their classifieds company

the Schmidt-Ruthenbeck family, majority shareholder of the Metro retail group (Stiftung Mercator)

the Hewlett family (co-founder of Hewlett-Packard), whose foundation is reputed to have around ten billion dollars in funds

Chris Hohn, whose Children Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF) is the result of his hedge fund fortune.

Firebreak editor’s note: Steve Ballmer’s foundation set up a climate wing in 2022 and, after this article was published, announced a $28 million donation to the ECF for 2023-25.

High-Level Board, Low-Level Transparency

The ECF does not publish the precise breakdown of its resources or expenses. However, it publicly displays its very high-level governance. Head of this organization of more than 200 employees, Laurence Tubiana is flanked by a "supervisory board" and an "advisory board". The first "approves the strategic direction and expenses related to the funds distributed and supervises the activities of the Foundation". In addition to Pascal Lamy, Connie Hedegaard and Sharan Burrow, it includes representatives of the donor foundations. Stephen Brenninkmeijer, heir and long-time boss of the clothing group, C&A, chaired it between 2018 and 2022, before handing over to the boss of the CIFF, the American Kate Hampton.

In 2019, long-time ECF companion, Caïo Koch-Weser, took over as head of a newly created “advisory board”. He sits on it alongside other “illustrious figures”, the ECF website specifies, such as Irish diplomat and former UN special envoy for climate change, Mary Robinson, the head of markets on the Bundesbank board, Sabine Mauderer (quite surprisingly), Brazilian Ana Toni, a legendary figure of Greenpeace, and British economist Nicholas Stern, author of the famous 2006 Stern Report on “the economics of climate change”. They “advise” the Foundation’s teams on “strategic direction and provide thematic input”.

… “a thematic input.”

“It takes three planets to plant forests”

The ECF “does not advocate for green growth per se but for the transition to an economy with net-zero greenhouse gas emissions”, explains one of its communicators. …

When asked about the limits of “net zero”, in other words: the accounting of “negative” emissions to offset real emissions, Pascal Lamy replied:

“I agree that if we look at everything that is purchased as forests and as compensation in the world and in companies’ balance sheets, it takes three planets to plant the forests. Obviously, there are problems of consistency. There are cases where compensation is excessive in the decarbonization process. I think that will adjust”.

Lamy is working on it with Emmanuel Faber, the former boss of Danone and “a close friend”, who is thinking about a “system of extra-accounting standards to validate, standardize and provide the necessary transparency”. Then Lamy added: “capitalism is moving in this direction”.

“Brussels” co-finances

From the generalization of carbon commodification to supporting the creation of derivatives on natural assets, including the revision of the prudential regulations of financial institutions based on environmental criteria, the European Green Deal is inspired by the same idea according to which the financial system will adapt and participate in limiting emissions.

The Commission seemed so confident in the future of green finance that it had been advised by the world’s largest asset manager, BlackRock, on the greening of these rules.

This BlackRock consulting contract caused a mini-scandal in 2021 and aroused the ire of the European ombudsman. At the time, the EUobserver website illustrated its review of the affair with a photo of a demonstration by “young people against the apocalypse” in front of Senator Feinstein’s office … in San Francisco.

BlackRock was built on wealth management. Philanthropists are its clients.

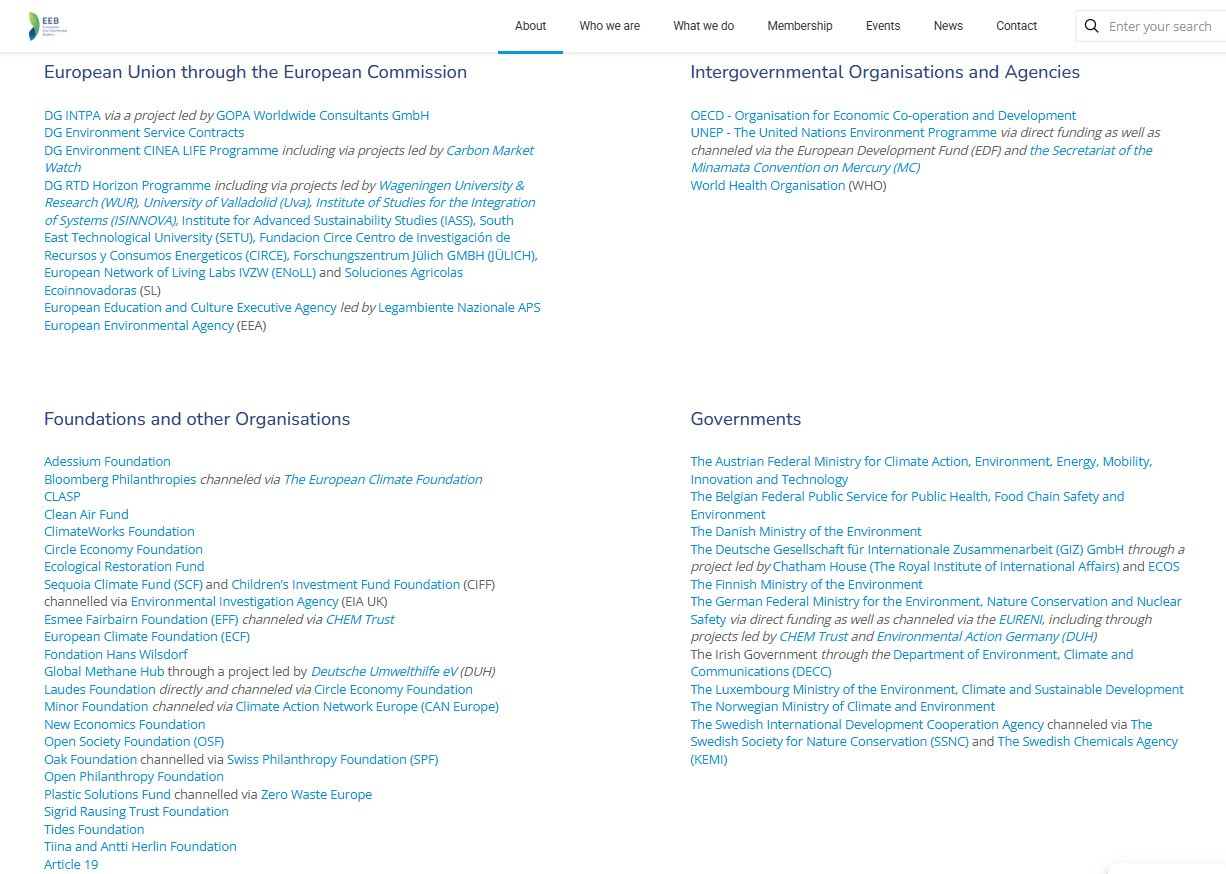

For years, the Commission has been co-financing the rise of "civil society", particularly through the LIFE programme. We are talking about millions of euros of public money given each year to organizations that only communicate. At the table of certain NGOs, we also find German, Dutch or Scandinavian national ministries or agencies, alongside private donors and the EU.

These public actors thus offer financial leverage to philanthropists whose foundations are nevertheless sitting on tens of billions of dollars invested who knows where, and who also have, in their own name, considerable asset portfolios.

Almost no one seems to care about the possible conflicts of interest that inevitably affect these billionaires, who are both "benefactors" of the planet AND investors. However, as Edouard Morena writes:

“A number of prominent climate philanthropies have embraced and promoted this approach and narrative [editor’s note: nature-based solutions and green technologies], including many whose endowments and boards are closely associated with tech and/or venture capital. They have backed (and continue to back) organizations and initiatives associated with market-based solutions (carbon markets or carbon offsets) and so-called negative-emissions technologies …”.

The Big Questions

One can only wonder about the way in which foundation endowment funds are invested, in particular whether they are likely to be invested in “natural assets” that are likely to be commodified or in technologies that could benefit from the political choices and public funding resulting from this climate agenda.

We must also wonder whether philanthropists are seeking, through NGO activism, to establish a balance of power with economic and financial actors like the asset manager BlackRock.

These are just hypothetical questions.

These great philanthropies, built on the fortunes of billionaires who only represent themselves, have unprecedented political influence. But they:

are not accountable to the financial interests of their foundations

do not give interviews on this subject

act under the title of the “public good” of their political activism vehicles

do not pay taxes on enormous sums.

In the absence of information on the assets in which these fortunes are invested, the possible biases and interests of the foundations’ actions cannot be identified.

Does Laurence Tubiana, with her six-figure salary as ECF CEO, know where her money is coming from? Or is she paid to pass over them in silence?